2 The Normal (and Related) Distributions

In this chapter, we illustrate probability and statistical inference concepts utilizing the normal distribution. The normal, also known in the physical sciences as the Gaussian distribution and, colloquially, the “bell curve,” is the most utilized probability distribution in data analyses.

- We often observe that the data that we generate in experiments are at least approximately normally distributed. And while other, more general families of distributions (such as the gamma distribution) might explain the data-generating process as well as the normal distribution does, it has the advantage of having intuitively easy-to-understand parameters: \(\mu\) for the mean, and \(\sigma^2\) for the variance (meaning that \(\sigma\) directly indicates the “width” of the region on the real-number line over which \(f_X(x)\) is effectively non-zero).

- The normal distribution is the limiting distibution for many other distributions (i.e., there are many families of distributions that, with the right choice(s) for parameter value(s), can mimic the shape of the normal).

- The normal distribution figures prominently in the Central Limit Theorem, which states that if we sample a sufficiently large number of data according to any distribution with finite variance, we can assume the sample mean to be approximately normally distributed.

2.1 Normal Distribution: Probability Density Function

Recall: a probability density function is one way to represent a continuous probablity distribution, and it has the properties (a) \(f_X(x) \geq 0\) and (b) \(\int_x f_X(x) dx = 1\), where the integral is over all values of \(x\) in the distribution’s domain.

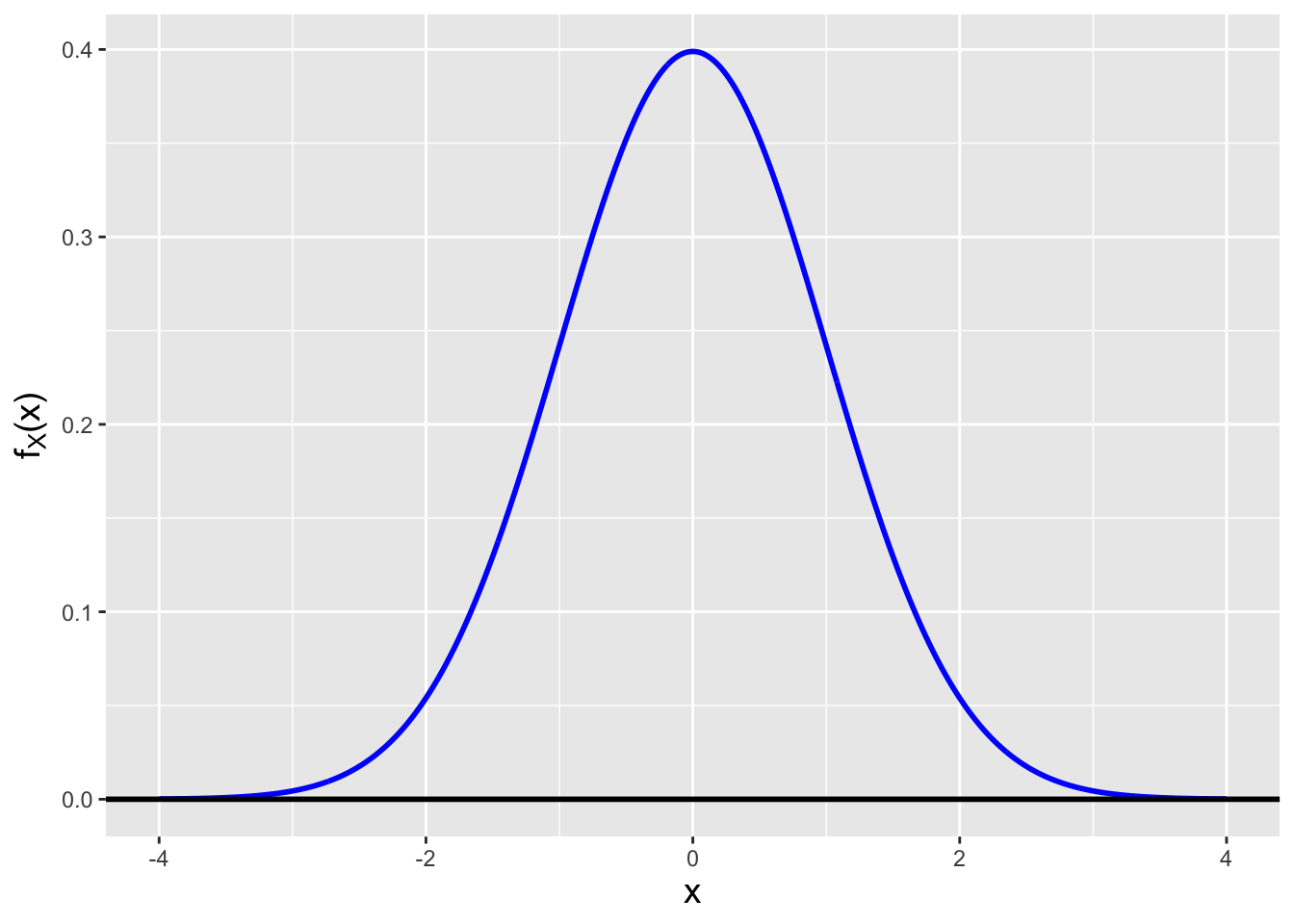

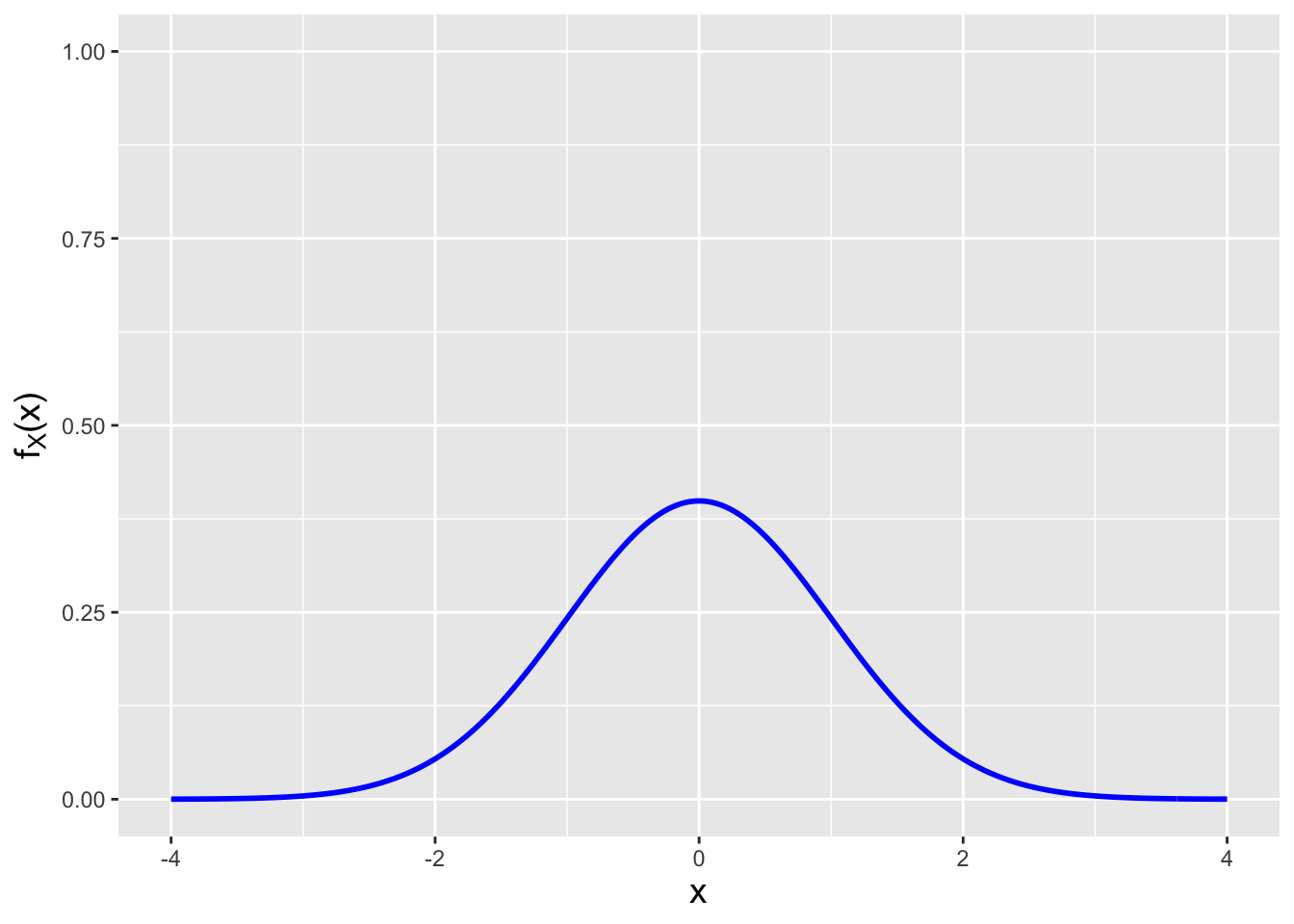

Let \(X\) be a continuous random variable sampled according to a normal distribution with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\), i.e., let \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\). The pdf for \(X\) is \[ f_X(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) ~~~~~~ x \in (-\infty,\infty) \,. \] This pdf is symmetric around \(\mu\) (see Figure 2.1), with the area under the curve approaching 1 over the range \(\mu - 3\sigma \leq x \leq \mu + 3\sigma\). (The value of the integral of \(f_X(x)\) over this range is 0.9973. This gives rise to one aspect of the so-called empirical rule: if data are sampled according to a normal or normal-like distribution, we expect (nearly) all of the data to lie with three standard deviations of the population mean.)

Figure 2.1: A normal probability density function with mean 0 and standard deviation 1.

2.1.1 Expected Value and Variance

Recall: the expected value of a continuously distributed random variable is \[ E[X] = \int_x x f_X(x) dx\,, \] where the integral is over all values of \(x\) within the domain of the pdf \(f_X(x)\). The expected value is equivalent to a weighted average, with the weight for each possible value of \(x\) given by \(f_X(x)\).

The expected value of a normal random variable \(X\) is \[ E[X] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty x \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \] To evaluate this integral, we implement variable substitution. Recall that the three steps of variable substitution are…

- to write down a viable substitution \(u = g(x)\);

- to then derive \(du = h(u,x) dx\); and finally

- to use \(u = g(x)\) to transform the bounds of the integral.

Because the integral bounds here are \(-\infty\) and \(\infty\), we choose \(u = g(x)\) such that we rewrite \((x-\mu)^2/\sigma^2\) as \(u^2\), so that eventually, as we will see, what remains in the integrand is a normal pdf for \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma^2 = 1\): \[ (1) ~~ u = \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} ~~ \implies ~~ (2) ~~ du = \frac{1}{\sigma}dx \] and \[ (3) ~~ x = -\infty ~\implies~ u = -\infty ~~~ \mbox{and} ~~~ x = \infty ~\implies~ u = \infty \,, \] Thus \[\begin{align*} E[X] &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty (\sigma u + \mu) \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{u^2}{2}\right) \sigma du \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sigma u}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{u^2}{2}\right) du + \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\mu}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{u^2}{2}\right) du \end{align*}\] The first integrand is the product of an odd function (\(u\)) and an even function (\(\exp(-u^2/2)\)), and thus the first integral evaluates to zero. As for the second integral: \[ E[X] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\mu}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{u^2}{2}\right) du = \mu \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{u^2}{2}\right) du = \mu \,. \] As stated above, the integrand is a normal pdf with parameters \(\mu = 0\) and \(\sigma^2\) = 1, and since the bounds of the integral match that of the domain of the normal pdf, the value of the integral is 1.

Recall: the variance of a continuously distributed random variable is \[ V[X] = \int_x (x-\mu)^2 f_X(x) dx = E[X^2] - (E[X])^2\,, \] where the integral is over all values of \(x\) within the domain of the pdf \(f_X(x)\). The variance represents the square of the “width” of a probability density function, where by “width” we mean the range of values of \(x\) for which \(f_X(x)\) is effectively non-zero.

Here, \(V[X] = E[X^2] - (E[X])^2 = E[X^2] - \mu^2\). To determine \(E[X^2]\), we implement a similar variable substitution to the one above, except that now \[\begin{align*} E[X^2] &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty (\sigma t + \mu)^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) \sigma dt \\ &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sigma^2 t^2}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) dt + \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{2 \mu \sigma t}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) dt + \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\mu^2}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) dt \,. \end{align*}\] The second integral is that of an odd function and thus evaluates to zero, and the third integral is, given results above, \(\mu^2\). This leaves \[ E[X^2] = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{\sigma^2 t^2}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) dt + \mu^2 \,. \] or \[ V[X] = \frac{\sigma^2}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty t^2 \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) dt \,. \] As the integrand is not a normal pdf, we need to pursue integration by parts. Setting aside the constants outside the integral, we have that \[ \begin{array}{ll} u = -t & dv = -t \exp(-t^2/2) dt \\ du = -dt & v = \exp(-t^2/2) \end{array} \,, \] and so \[\begin{align*} \int_{-\infty}^\infty t^2 \exp\left(-\frac{t^2}{2}\right) dt &= \left. uv \right|_{-\infty}^{\infty} - \int_{-\infty}^\infty v du \\ &= - \left. t \exp(-t^2/2) \right|_{-\infty}^{\infty} + \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp(-t^2/2) dt \\ &= 0 + \sqrt{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp(-t^2/2) dt \\ &= \sqrt{2\pi} \,. \end{align*}\] The first term evaluates to zero between for each bound, as \(e^{-t^2/2}\) goes to zero much faster than \(\vert t \vert\) goes to infinity. As for the second term: we recognize that the integrand is a normal pdf with mean zero and variance one…so the integral by definition evaluates to 1. In the end, after restoring the constants we set aside above, we have that \[ V[X] = \frac{\sigma^2}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} \sqrt{2\pi} = \sigma^2 \,. \]

2.1.2 Skewness

The skewness of a pmf or pdf is a metric that indicates its level of asymmetry. Fisher’s moment coefficient of skewness is \[ E\left[\left(\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^3\right] \,. \] which, expanded out, becomes \[ \frac{E[X^3] - 3 \mu \sigma^2 - \mu^3}{\sigma^3} \,. \] What is the skewness of the normal distribution? At first, this appears to require a long and involved series of integrations so as to solve \(E[X^3]\). But let’s try to be more clever.

We know, from above, that the quantity \((\sigma t + \mu)^3\) will appear in the integral for \(E[X^3]\). Let’s expand this out: \[ \sigma^3 t^3 + 3 \sigma^2 \mu t^2 + 3 \sigma \mu^2 t + \mu^3 \,. \] Each of these terms will appear separately in integrals of \(\exp(-t^2/2)/\sqrt{2\pi}\) over the domain \(-\infty\) to \(\infty\). From above, what do we already know? First, we know that if \(t\) is raised to an odd power, the integral will be zero. This eliminates \(\sigma^3 t^3\) and \(3 \sigma \mu^2 t\). Second, we know that for the \(t^0\) term, the result will be \(\mu^3\), and we know that for the \(t^2\) term, the result will be \(3 \sigma^2 \mu\). Thus \[ E[X^3] = 3\sigma^2\mu + \mu^3 \] and the skewness is \[ \frac{3 \mu \sigma^2 + \mu^3 - 3 \mu \sigma^2 - \mu^3}{\sigma^3} = 0 \,. \] The skewness is zero, meaning that a normal pdf is symmetric around its mean \(\mu\).

2.1.3 Computing Probabilities

Before diving into this example, we will be clear that this is not the optimal way to compute probabilities associated with normal random variables, as we should utilize

R’spnorm()function, as shown in the next section. However, showing how to utilizeintegrate()is useful review. (We also show how to pass distribution parameters tointegrate(), which we did not do in the last chapter.)

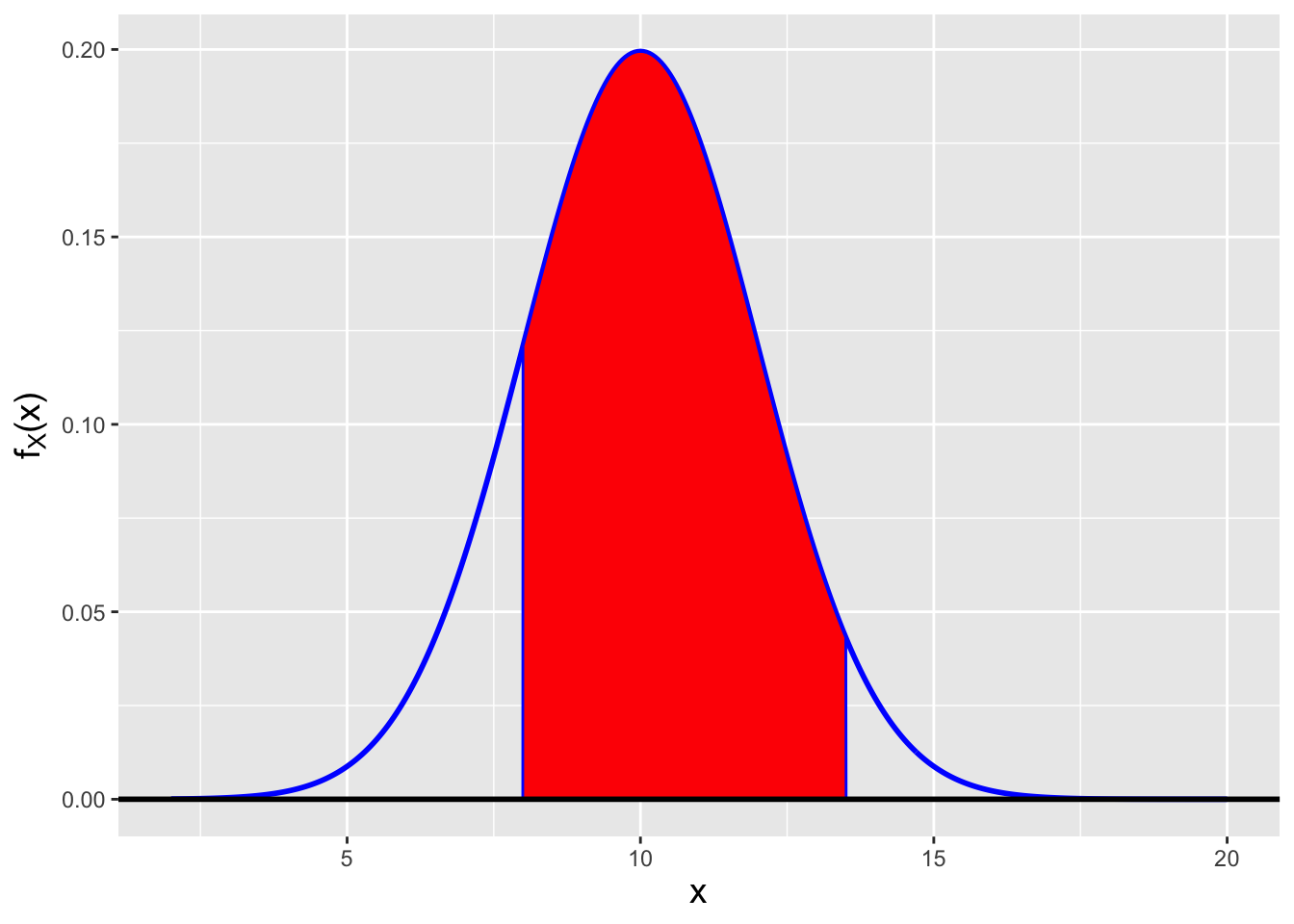

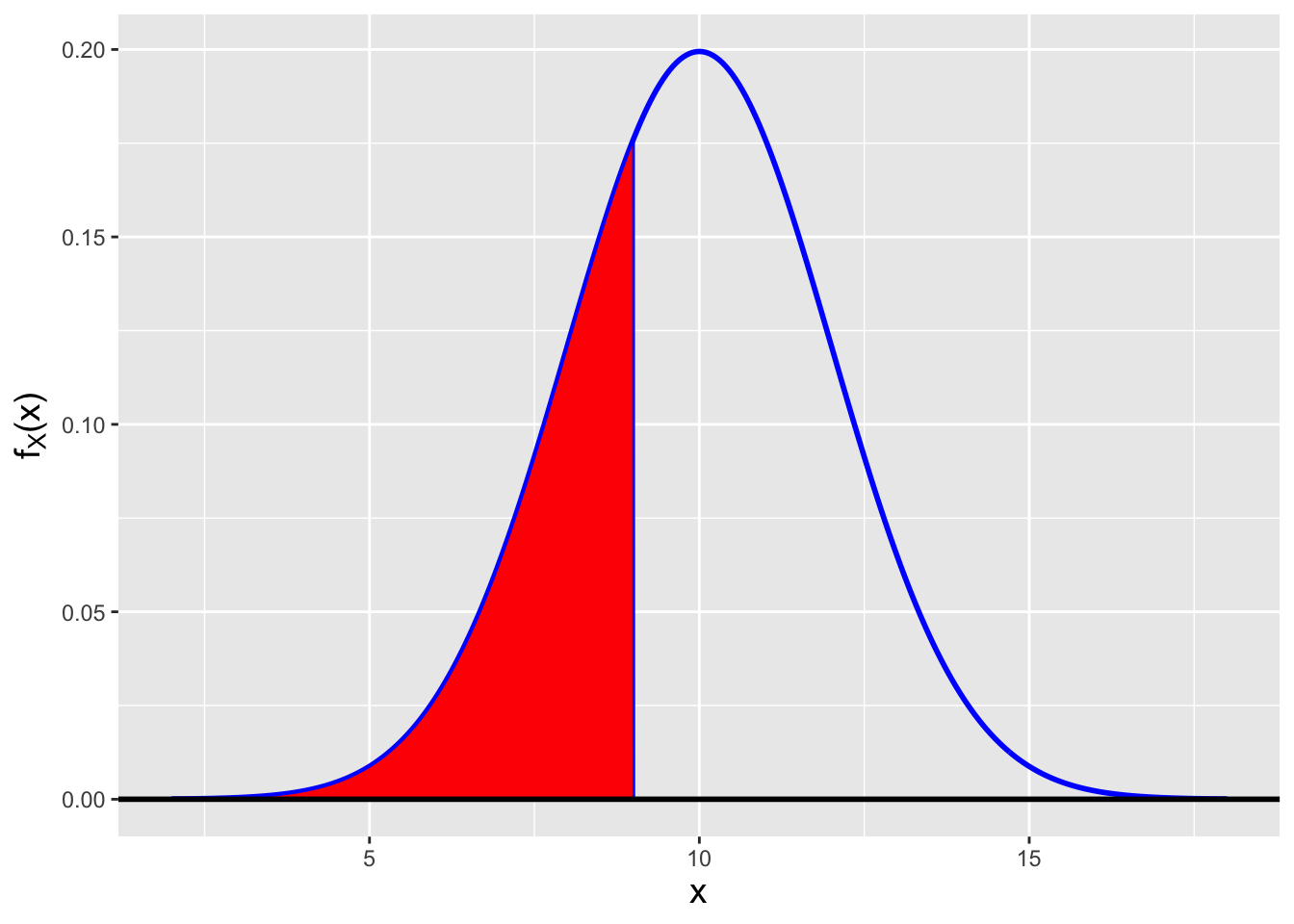

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(10,4)\), what is \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5)\)?

To find this probability, we integrate over the normal pdf with mean \(\mu = 10\) and variance \(\sigma^2 = 4\). Visually, we are determining the area of the red-shaded region in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: The probability \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5)\) is the area of the red-shaded region, i.e., the integral of the normal probability density function from 8 to 13.5, assuming \(\mu = 10\) and \(\sigma^2 = 4\).

integrand <- function(x,mu,sigma2) {

return(exp(-(x-mu)^2/2/sigma2)/sqrt(2*pi*sigma2))

}

integrate(integrand,8,13.5,mu=10,sigma2=4)$value## [1] 0.8012856The result is 0.801. Note how the

integrand()function requires extra information above and beyond the value ofx. This information is passed in using the extra argumentsmuandsigma2, the values of which are set in the call tointegrate().

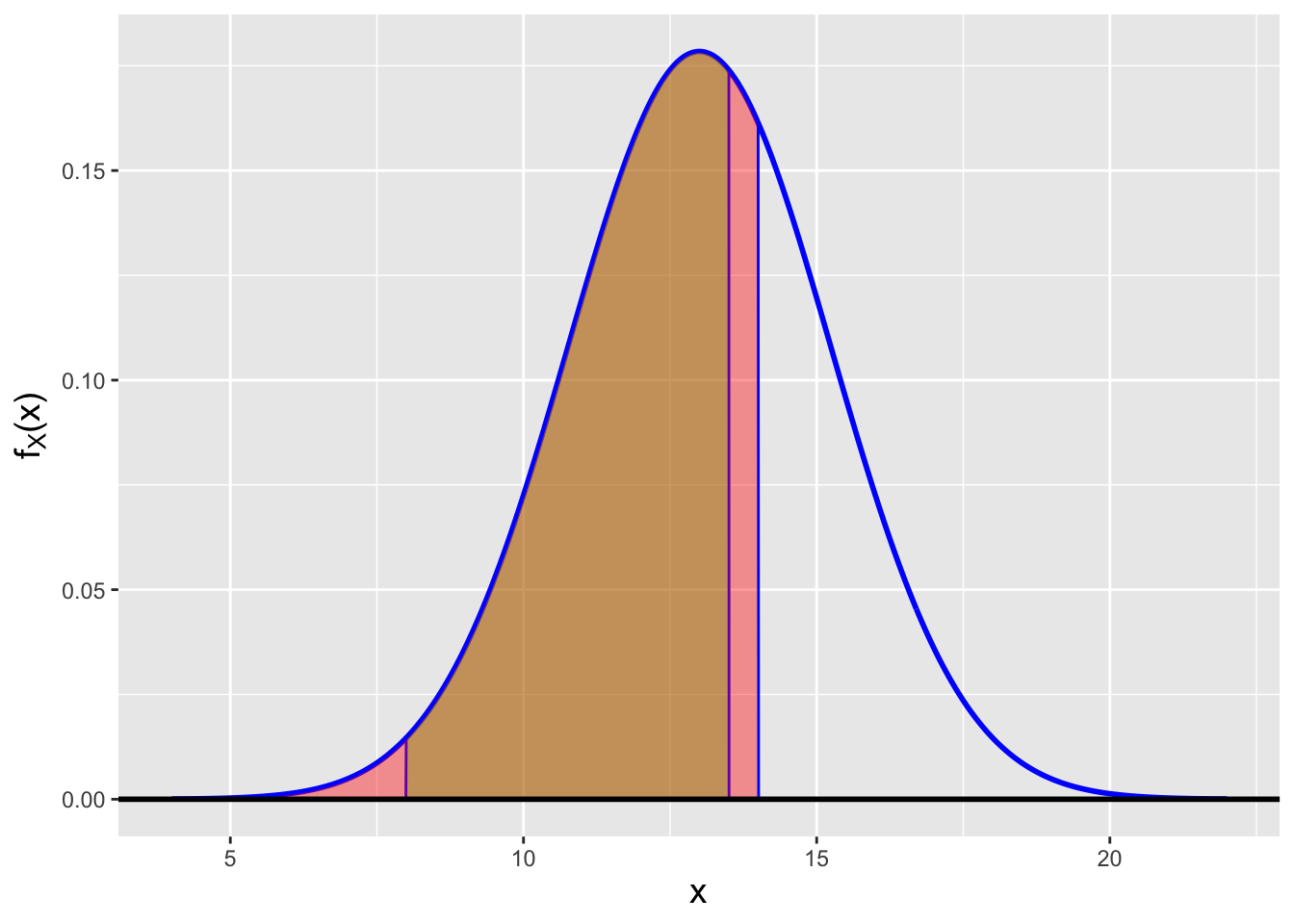

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(13,5)\), what is \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5 \vert X < 14)\)?

Recall that \(P(a \leq X \leq b \vert X \leq c) = P(a \leq X \leq b)/P(X \leq c)\), assuming that \(a < b < c\). So this probability is, visually, the ratio of the area of the brown-shaded region in Figure 2.3 to the area of the red-shaded region underlying it. We can reuse the

integrand()function from above, calling it twice:

integrate(integrand,8,13.5,mu=13,sigma2=5)$value /

integrate(integrand,-Inf,14,mu=13,sigma2=5)$value## [1] 0.8560226The result is 0.856. Note how we use

-Infin the second call tointegrate():Inf, likepi, is a reserved word in theRprogramming language.

Figure 2.3: The conditional probability \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5 \vert X < 14)\) is the ratio of the area of the brown-shaded region to the area of the red-shaded region underlying the brown-shaded region.

2.2 Normal Distribution: Cumulative Distribution Function

Recall: the cumulative distribution function, or cdf, is another means by which to encapsulate information about a probability distribution. For a continuous distribution, it is defined as \(F_X(x) = \int_{y \leq x} f_Y(y) dy\), and it is defined for all values \(x \in (-\infty,\infty)\), with \(F_X(-\infty) = 0\) and \(F_X(\infty) = 1\).

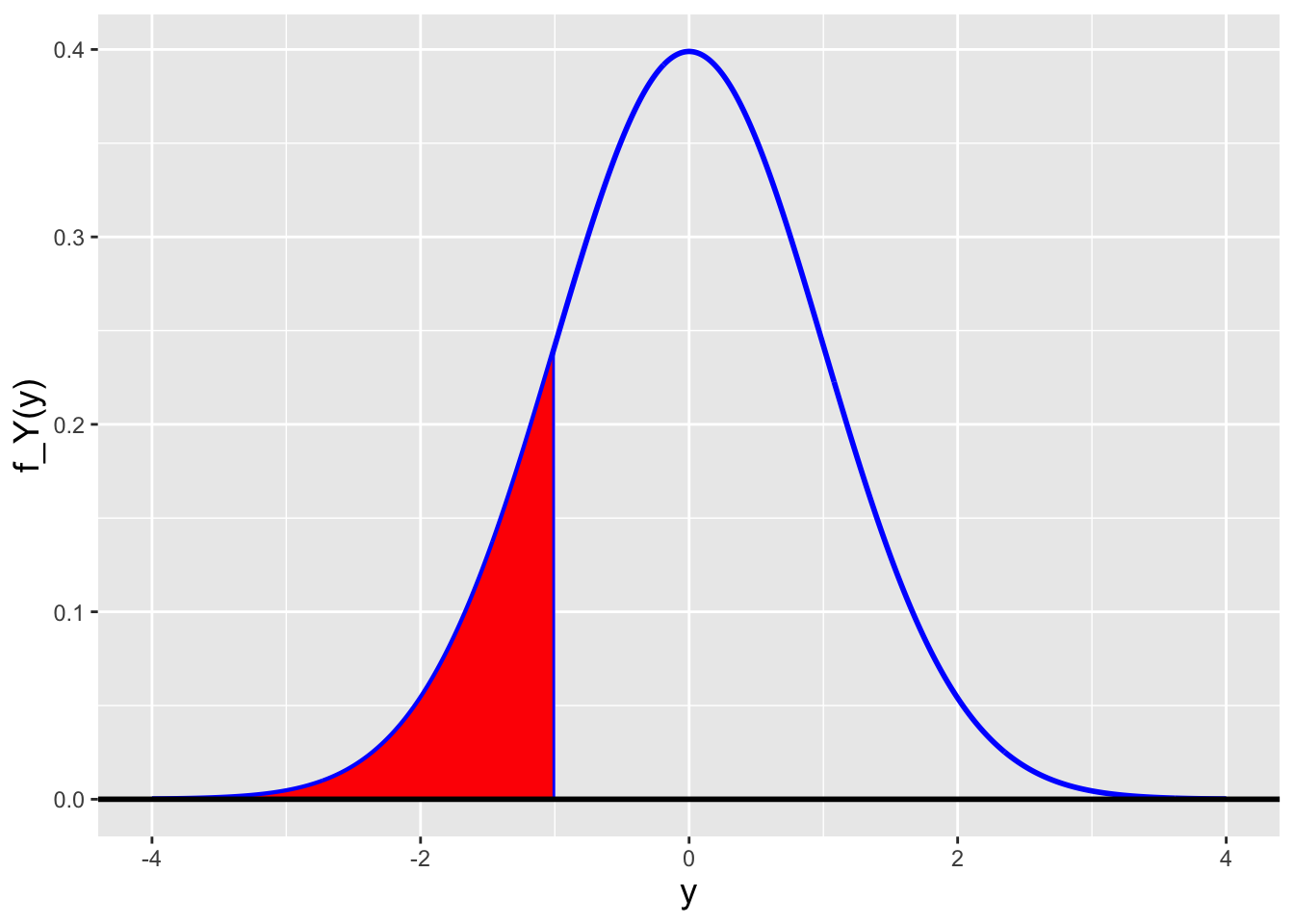

The cdf for the normal distribution is the “accumulated probability” between \(-\infty\) and the functional input \(x\): \[ F_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_Y(y) dy = \int_{-\infty}^x \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(y-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dy \,. \] (See Figure 2.4.) Recall that because \(x\) is the upper bound of the integral, we have to replace \(x\) with some other variable in the integrand itself. (Here we choose \(y\). The choice is arbitrary.)

Figure 2.4: The cdf is the area of the red-shaded polygon.

To evaluate this integral, we

again implement a variable substitution strategy:

\[

(1) ~~ t = \frac{(y-\mu)}{\sqrt{2}\sigma} ~~\implies~~ (2) ~~ dt = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}dy

\]

and

\[

(3) ~~ y = -\infty ~\implies~ t = -\infty ~~~ \mbox{and} ~~~ y = x ~\implies~ t = \frac{(x-\mu)}{\sqrt{2}\sigma} \,,

\]

so

\[\begin{align*}

F_X(x) &= \int_{-\infty}^x \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(y-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dy \\

&= \int_{-\infty}^{\frac{x-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \exp(-t^2) \sqrt{2}\sigma dt = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^{\frac{x-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}} \exp(-t^2) dt \,.

\end{align*}\]

The error function is defined as

\[

\mbox{erf}(z) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^z \exp(-t^2)dt \,,

\]

which is close to, but not quite, our expression for \(F_X(x)\). (The integrand is the same, but the bounds of integration differ.) To match the bounds:

\[\begin{align*}

\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^z \exp(-t^2)dt &= \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \left( \int_{-\infty}^0 \exp(-t^2)dt + \int_0^z \exp(-t^2)dt \right) \\

&= \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \left( -\int_0^{-\infty} \exp(-t^2)dt + \int_0^z \exp(-t^2)dt \right) \\

&= -\mbox{erf}(-\infty) + \mbox{erf}(z) = \mbox{erf}(\infty) + \mbox{erf}(z) = 1 + \mbox{erf}(z) \,.

\end{align*}\]

Here we make use of two properties of the error function: \(\mbox{erf}(-z) = -\mbox{erf}(z)\), and \(\mbox{erf}(\infty)=1\). Thus

\[

\frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^z \exp(-t^2)dt = \frac{1}{2}[1 + \mbox{erf}(z)] \,.

\]

By matching this expression with that given for \(F(x)\) above, we see that

\[

F_X(x) = \frac{1}{2}\left[1 + \mbox{erf}\left(\frac{x-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right)\right] \,.

\]

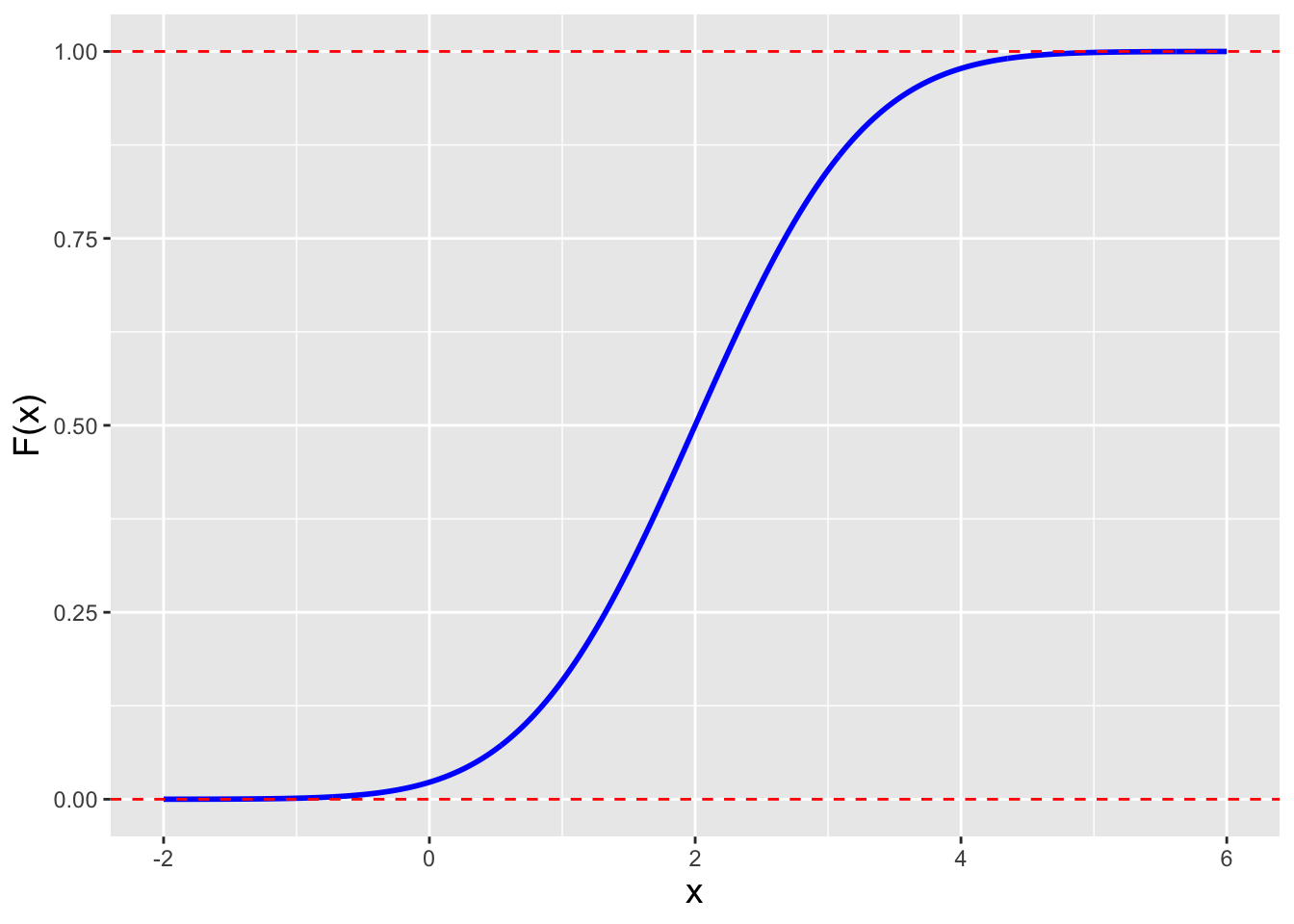

In Figure 2.5, we plot \(F_X(x)\).

We note that while the error function is available to use directly in

some R packages, it is provided only indirectly in base-R,

via the pnorm() function. (In general, one computes cdf values for

probability distributions in R using functions prefixed with p:

pnorm(), pbinom(), punif(), etc.) Examining this figure,

we see that this cdf abides by the properties listed in the previous

chapter: \(F(-\infty) = 0\) and \(F(\infty) = 1\), and it is (strictly)

monotonically increasing.

Figure 2.5: The cdf for a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1.

To compute the probability \(P(a < X < b)\), we make use of the cdf. (As

a reminder: if we have the cdf at our disposal and

need to compute a probability…we should use it!)

\[\begin{align*}

P(a < X < b) &= P(X < b) - P(X < a) \\

&= F(b) - F(a) = \frac{1}{2}\left[ \mbox{erf}\left(\frac{b-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right) - \mbox{erf}\left(\frac{a-\mu}{\sqrt{2}\sigma}\right)\right] \,,

\end{align*}\]

which is more simply rendered in R as

pnorm(b,mean=mu,sd=sigma) - pnorm(a,mean=mu,sd=sigma)Let’s look again at Figure 2.4. What if, instead of asking the question “what is the shaded area under the curve,” which is answered by integrating the normal pdf from \(-\infty\) to a specified coordinate \(x\), we instead ask the question “what value of \(x\) is associated with a given area under the curve”? This is the inverse problem, one that we can solve so long as the relationship between \(x\) and \(F(x)\) is bijective (i.e., one-to-one): \(x = F_X^{-1}[F_X(x)]\) for all \(x\).

Recall: an inverse cdf function \(F_X^{-1}(q)\) takes as input a distribution quantile \(q \in [0,1]\) and returns the value of \(x\) such that \(q = F_X(x)\).

Let \(q = F_X(x)\). Then, for the case of the normal cdf, we can write that

\[

x = \sqrt{2} \sigma~ \mbox{erf}^{-1}\left(2q-1\right) + \mu \,,

\]

where \(\mbox{erf}^{-1}(\cdot)\) is the inverse error function. Like the error function itself, the inverse error function is available for use in some R packages, but

it is most commonly accessed, indirectly via the base-R function qnorm(). (In general, one computes inverse cdf values for probability

distributions in R using functions prefixed with q: qnorm(), qpois(), qbeta(), etc.)

2.2.1 Computing Probabilities

We utilize the two examples provided in the last section to show how one would compute probabilities associated with the normal pdf by hand. But we note that a computer is still needed to derive the final numbers!

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(10,4)\), what is \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5)\)?

We have that \[ P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5) = P(X \leq 13.5) - P(X \leq 8) = F_X(13.5 \vert 10,4) - F_X(8 \vert 10,4) \,. \] Well, this is where analytic computation ends, as we cannot evaluate the cdfs using pen and paper. Instead, we utilize the function

pnorm():

## [1] 0.8012856We get the same result as we got in the last section: 0.801.

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(13,5)\), what is \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5 \vert X < 14)\)?

Knowing that we cannot solve this by hand, we go directly to

R:

## [1] 0.8560226The answer, as before, is 0.856.

But let’s go ahead and add some complexity here. How would we answer the following question?

- If \(\mu = 20\) and \(\sigma^2 = 3\), what is the value of \(a\) such that \(P(20 - a \leq X \leq 20 + a) = 0.48\)?

(The first thing to thing about here is: does the value of \(\mu\) actually matter? The answer here is no. Think about why that may be.)

We have that \[\begin{align*} P(20-a \leq X \leq 20+a) = 0.48 &= P(X \leq 20+a) - P(X \leq 20-a)\\ &= F_X(20+a \vert 20,3) - F_X(20-a \vert 20,3) \,. \end{align*}\] Hmm…we’re stuck. We cannot invert this equation so as to isolate \(a\)…or can we? Remember that a normal pdf is symmetric around the mean. Hence \[ P(X \leq 20+a) = 1 - P(X > 20+a) = 1 - P(X \leq 20-a) \,. \] The area under the normal pdf from \(20+a\) to \(\infty\) is the same as the area from \(-\infty\) to \(20-a\). So… \[\begin{align*} P(20-a \leq X \leq 20+a) &= 1 - F_X(20-a \vert 20,3) - F_X(20-a \vert 20,3)\\ &= 1 - 2F_X(20-a \vert 20,3) \,, \end{align*}\] or \[ F_X(20-a \vert 20,3) = \frac{1}{2}[1 - P(20-a \leq X \leq 20+a)] = \frac{1}{2} 0.52 = 0.26 \,. \] Now, we invert the cdf and rearrange terms to get: \[ a = 20 - F_X^{-1}(0.26 \vert 20,3) \,, \] and once again, we transition to

R:

The result is \(a = 1.114\), i.e., \(P(18.886 \leq X \leq 21.114) = 0.48\).

The reader might quibble with our assertion that \(\mu\) doesn’t matter here, because, after all, the value of \(\mu\) appears in the final code. However, if we changed both values of 20 to some other, arbitrary value, we would derive the same value for \(a\).

2.2.2 Visualization

Let’s say we want to make a figure like that in Figure 2.4, where we are given that our normal distribution has mean \(\mu = 10\) and variance \(\sigma^2 = 4\), and we want to overlay the shaded region associated with \(F_X(9)\). How do we do this?

The first step is to determine the population standard deviation. Here, that would be \(\sigma = \sqrt{4} = 2\).

The second step is to determine an appropriate range of values of \(x\) over which to plot the cdf. Here we will assume that \(\mu - 4\sigma\) to \(\mu + 4\sigma\) is sufficient; this corresponds to \(x = 2\) to \(x = 18\).

The third step is to code. The result of our coding is shown in Figure 2.6.

x <- seq(2,18,by=0.05) # vector with x = {2,2.05,2.1,...,18}

f.x <- dnorm(x,mean=10,sd=2) # compute f(x) for all x

df <- data.frame(x=x,f.x=f.x) # define a dataframe with above data

df.shaded <- subset(df,x<=9) # get subset of data with x values <= 9

ggplot(data=df,aes(x=x,y=f.x)) +

geom_line(col="blue",lwd=1) +

geom_area(data=df.shaded,fill="red",col="blue",outline.type="full") +

geom_hline(yintercept=0,lwd=1) +

labs(y = expression(f[X]*"(x)")) +

theme(axis.title=element_text(size = rel(1.25)))

Figure 2.6: The cumulative distribution function is the area of the red-shaded region.

For the polygon, the first \((x,y)\) pair is \((9,0)\), the second is \((2,0)\) (where \(x = 2\) is the lower limit of the plot…there is no need to take the polygon further “to the left”), and the next set are \((x,f_X(x))\) for all \(x\) values \(\leq 9\). The last point is the first point: this closes the polygon.

2.3 Method of Moment-Generating Functions

In the previous chapter, we learned that if we linearly transform a random variable, i.e., if we define a new random variable \(Y = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i + b\), where \(\{a_1,\ldots,a_n\}\) and \(b\) are constants, then \[ E[Y] = E\left[\sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i + b\right] = b + \sum_{i=1}^n a_i E[X_i] \,. \] Furthermore, if we assume that the \(X_i\)’s are independent random variables, then the variance of \(Y\) is \[ V[Y] = V\left[\sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i + b\right] = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2 V[X_i] \,. \] (Because the \(X_i\)’s are independent, we do not need to take into account any covariance, or linear dependence, between the \(X_i\)’s, simplifying the equation for \(V[Y]\). We discuss how covariance is taken into account in Chapter 6.) So we know where \(Y\) is centered and we know how “wide” it is. However, we don’t yet know the shape of the distribution for \(Y\), i.e., we don’t yet know \(f_Y(y)\). To show how we might derive the distribution, we introduce a new concept, that of the moment-generating function, or mgf.

In the previous chapter, we introduced the concept of distribution moments, i.e., the expected values \(E[X^k]\) and \(E[(X-\mu)^k]\). The moments of a given probability distribution are unique, and can often (but not always) be neatly encapsulated in a single mathematical expression: the moment-generating function (or mgf). To derive an mgf for a given distribution, we invoke the Law of the Unconscious Statistician: \[\begin{align*} m_X(t) = E[e^{tX}] &= \int_x e^{tX} f_X(x) \\ &= \int_x \left[1 + tx + \frac{t^2}{2!}x^2 + \cdots \right] f_X(x) \\ &= \int_x \left[ f_X(x) + t x f_X(x) + \frac{t^2}{2!} x^2 f_X(x) + \cdots \right] \\ &= \int_x f_X(x) + t \int_x x f_X(x) + \frac{t^2}{2!} \int_x x^2 f_X(x) + \cdots \\ &= 1 + t E[X] + \frac{t^2}{2!} E[X^2] + \cdots \,. \end{align*}\] An mgf only exists for a particular distribution if there is a constant \(b\) such that \(m_X(t)\) is finite for \(\vert t \vert < b\). (This is a detail that we will not concern ourselves with here, i.e., we will assume that the expressions we derive for \(E[e^{tX}]\) are valid expressions.) An example of a distribution for which the mgf does not exist is the Cauchy distribution.

Moment-generating functions are called such because, as one might guess, they generate moments (via differentiation): \[ \left.\frac{d^k m_X(t)}{dt^k}\right|_{t=0} = \frac{d^k}{dt^k} \left. \left[1 + t E[X] + \frac{t^2}{2!} E[X^2] + \cdots \right]\right|_{t=0} = \left. \left[E[X^k] + tE[X^{k+1}] + \cdots\right] \right|_{t=0} = E[X^k] \,. \] The \(k^{\rm th}\) derivative of an mgf, with \(t\) set to zero, yields the \(k^{\rm th}\) moment \(E[X^k]\).

But, the reader may ask, why are mgfs important here, in the context of normal random variables? We already know all the moments of this distribution that we care to know: they are written down (or can be derived directly via the integration of \(x^k f_X(x)\)). The answer is that a remarkably useful property of mgfs is the following: if \(Y = b + \sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i\), where the \(X_i\)’s are independent random variables sampled according to a distribution whose mgf exists, then \[ m_Y(t) = e^{bt} m_{X_1}(a_1 t) m_{X_2}(a_2 t) \cdots m_{X_n}(a_n t) = e^{bt} \prod_{i=1}^n m_{X_i}(a_i t) \,, \] where \(m_{X_i}(\cdot)\) is the moment-generating function for the random variable \(X_i\). An mgf is typically written as a function of \(t\); the notation \(m_{X_i}(a_it)\) simply means that when we evaluate the above equation, wherever there is a \(t\), we plug in \(a_it\). Here’s the key point: if we recognize the form of \(m_Y(t)\) as matching that of the mgf for a given distribution, then we know the distribution for \(Y\).

Below, we show how the method of moment-generating functions allows us to derive distributions for linearly transformed normal random variables.

2.3.1 MGF: Probability Mass Function

Let’s assume that we sample data from the following pmf:

| \(x\) | \(p_X(x)\) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.2 |

| 1 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 0.5 |

What is the mgf for this distribution? What is its expected value? If we sample two data, \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), independently from this distribution, what is the mgf of the sampling distribution for \(Y = 2X_1 - X_2\)?

To derive the mgf, we compute \(E[e^{tX}]\): \[ m_X(t) = E[e^{tX}] = \sum_x e^{tx} p_X(x) = 1 \cdot 0.2 + e^t \cdot 0.3 + e^{2t} \cdot 0.5 = 0.2 + 0.3 e^t + 0.5 e^{2t} \,. \] This cannot be simplified, and thus this is the final answer. As far as the expected value is concerned: we could simply compute \(E[X] = \sum_x x p_X(x)\), but since we have the mgf now, we can use it too: \[ E[X] = \left.\frac{d}{dt}m_X(t)\right|_{t=0} = \left. (0.3 e^t + e^{2t})\right|_{t=0} = 0.3 + 1 = 1.3 \,. \] As for the linear function \(Y = 2X_1 - X_2\): if we refer back to the equation above, we see that \[\begin{align*} m_Y(t) &= e^{bt} m_{X_1}(a_1t) m_{X_2}(a_2t) = e^{0t} m_{X_1}(2t) m_{X_2}(-1t) \\ &= \left(0.2 + 0.3e^{2t} + 0.5e^{4t}\right) \left(0.2 + 0.3e^{-t} + 0.5e^{-2t}\right) \\ &= 0.19 + 0.10 e^{-2t} + 0.06 e^{-t} + 0.09 e^t + 0.31 e^{2t} + 0.15 e^{3t} + 0.10 e^{4t} \,. \end{align*}\]

2.3.2 MGF: Probability Density Function

Let’s assume that we now sample data from the following pdf: \[ f_X(x) = \frac{1}{\theta} e^{-x/\theta} \,, \] where \(x \geq 0\) and \(\theta > 0\). What is the mgf of this distribution? If we sample two data, \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), independently from this distribution, what is the mgf of the sampling distribution for \(Y = X_1 + X_2\)?

To derive the mgf, we compute \(E[e^{tX}]\): \[\begin{align*} E[e^{tX}] &= \int_0^\infty e^{tx} \frac{1}{\theta} e^{-x/\theta} dx = \frac{1}{\theta} \int_0^\infty e^{-x\left(\frac{1}{\theta}-t\right)} dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\theta} \int_0^\infty e^{-x/\theta'} dx = \frac{\theta'}{\theta} = \frac{1}{\theta} \frac{1}{(1/\theta - t)} = \frac{1}{(1-\theta t)} = (1-\theta t)^{-1} \,. \end{align*}\] The expected value of this distribution can be computed via the integral \(\int_x x f_X(x) dx\), but again, as we now have the mgf, \[ E[X] = \left.\frac{d}{dt}m_X(t)\right|_{t=0} = \left. -(1-\theta t)^{-2} (-\theta)\right|_{t=0} = \theta \,. \] As for the linear function \(Y = X_1 + X_2\): if we refer back to the equation above, we see that \[\begin{align*} m_Y(t) &= e^{bt} m_{X_1}(a_1t) m_{X_2}(a_2t) = e^{0t} m_{X_1}(t) m_{X_2}(t) \\ &= (1-\theta t)^{-1} (1-\theta t)^{-1} = (1 - \theta t)^{-2} \,. \end{align*}\] While the reader would not know this yet, this is the mgf for a gamma distribution with shape parameter \(a = 2\) and scale parameter \(b = \theta\). We will discuss the gamma distribution in Chapter 4.

2.3.3 MGF: Normal Distribution

The moment-generating function for a normal distribution is \[\begin{align*} m_X(t) = E[e^{tX}] &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{tx} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(x(\frac{\mu}{\sigma^2}+t)\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{x\mu'}{\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \,, \end{align*}\] where \(\mu' = \mu + t\sigma^2\). To solve this integral, we utilize the method of “completing the square.” We know that \[ (x - \mu')^2 = x^2 - 2x\mu' + (\mu')^2 \,, \] so we will introduce a new term that is equal to 1 into the integrand: \[ \exp\left(-\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \,. \] Now we have that \[\begin{align*} m_X(t) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{x\mu'}{\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{2x\mu'}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \,. \end{align*}\] The integral disappears because it is the integral of the pdf for a \(\mathcal{N}(\mu',\sigma^2)\) distribution over its entire domain; that integral is 1. Continuing… \[\begin{align*} m_X(t) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{x\mu'}{\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{2x\mu'}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \int_{-\infty}^\infty \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) dx \\ &= \exp\left(\frac{(\mu')^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) = \exp\left(\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{2\mu\sigma^2t}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(\frac{\sigma^4t^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{\mu^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \\ &= \exp\left(\mu t\right) \exp\left(\frac{\sigma^2t^2}{2}\right) = \exp\left(\mu t + \frac{\sigma^2t^2}{2} \right) \,. \end{align*}\] We will utilize this function in the next section below to derive the mgfs for linear functions of normal random variables.

2.4 Normal Distribution: Sample Mean

Suppose we are given \(n\) normal random variables \(\{X_1,\ldots,X_n\}\), which are independent (but, for now, not necessarily identically distributed), and we wish to determine the distribution of the sum \(Y = b + \sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i\). As shown above, the moment-generating function for any one of the random variables is \[ m_{X_i}(t) = \exp\left(\mu_i t + \sigma_i^2\frac{t^2}{2} \right) \,. \] Thus, by the method of moment-generating functions, \[\begin{align*} m_Y(t) &= \exp(bt) \prod_{i=1}^n m_{X_i}(a_it) \\ &= \exp(bt) \exp\left(\mu_1a_1t+a_1^2\sigma_1^2\frac{t^2}{2}\right) \cdot \cdots \cdot \exp\left(\mu_na_nt+a_n^2\sigma_n^2\frac{t^2}{2}\right) \\ &= \exp\left[ (b+a_1\mu_1+\cdots+a_n\mu_n)t + \left(a_1^2\sigma_1^2 + \cdots + a_n^2\sigma_n^2\right)\frac{t^2}{2} \right] \\ &= \exp\left[ \left(b+\sum_{i=1}^n a_i\mu_i\right)t + \left(\sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2\sigma_i^2\right)\frac{t^2}{2} \right] \,. \end{align*}\] The result retains the functional form of a normal mgf, and thus we conclude that \(Y\) itself is a normally distributed random variable, with mean \(b+\sum_{i=1}^n a_i\mu_i\) and variance \(\sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2\sigma_i^2\): \[ Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(b+\sum_{i=1}^n a_i\mu_i,\sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2\sigma_i^2\right) \,. \] If the data are identically distributed, then we can re-express the above as \[ Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(b+(\sum_{i=1}^n a_i)\mu,(\sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2)\sigma^2\right) \,. \] We will utilize this second result extensively…and we will start by looking at the sample mean.

If \(Y = \bar{X} = (\sum_{i=1}^n X_i)/n\), then \(b = 0\) and each of the \(a_i\)’s is \(1/n\). Thus \[ Y = \bar{X} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mu \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{n},\sigma^2 \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{n^2} \right) ~~~~~~\mbox{or}~~~~~~ \bar{X} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mu,\frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right) \,. \] We see that the sample mean that we observe in any given experiment is drawn according to a normal distribution that is centered on the true mean and that has a width that goes to zero as \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

2.4.1 Computing Probabilities

Let \(X_1 \sim \mathcal{N}(10,4^2)\) and \(X_2 \sim \mathcal{N}(8,2^2)\) be two independent random variables, and let \(Y = X_1 - X_2\). What is \(P(0 \leq Y \leq 2)\)?

From above, we see that \[ Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(b + \sum_{i=1}^n a_i \mu_i,\sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2 \sigma_i^2\right) ~~~ \Rightarrow ~~~ Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(10-8,4^2+2^2\right) ~~~ Y \sim \mathcal{N}(2,20) \,. \] Thus the probability we seek is \[ P(0 \leq Y \leq 2) = P(Y \leq 2) - P(Y \leq 0) = F_Y(2) - F_Y(0) \,, \] or

## [1] 0.1726396There is a 17.3% chance that when we sample \(X_1\) and \(X_2\), the difference \(X_1 - X_2\) has a value between 0 and 2.

2.5 Normal Distribution: Standardization

To standardize a random variable that is sampled according to any distribution, we subtract off its expected value and then divide by its standard deviation: \[ Z = \frac{X - E[X]}{\sqrt{V[X]}} \,. \] If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\), and thus if \(Z = (X-\mu)/\sigma\), what is \(f_Z(z)\)? Going back to the result we wrote down above, \[ Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(b+(\sum_{i=1}^n a_i)\mu,(\sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2)\sigma^2\right) \,. \] Here, \(Y = Z\), with \(n=1\), \(a_1 = 1/\sigma\), and \(b = -\mu/\sigma\). Thus \[ Z \sim \mathcal{N}\left(-\frac{\mu}{\sigma}+\frac{1}{\sigma}\mu,\frac{1}{\sigma^2}\sigma^2\right) ~~~~~~\mbox{or}~~~~~~ Z \sim \mathcal{N}\left(0,1\right) \,. \] \(Z\) is a standard normal random variable. Its probability density function is \[ f_Z(z) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{z^2}{2}\right) ~~~~ z \in (-\infty,\infty) \,, \] while its cumulative distribution function is \[ F_Z(z) = \Phi(z) = \frac{1}{2}\left[1 + \mbox{erf}\left(\frac{z}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right] \,. \] By historical convention, the cdf of the standard normal distribution is denoted \(\Phi(z)\) (“phi” of z, pronounced “fye”) rather than \(F_Z(z)\).

Statisticians often standardize normally distributed random variables and perform probability calculations using the standard normal. Strictly speaking, standardization is unnecessary in the age of computers, but in the pre-computer era standardization greatly simplified probability calculations since all one needed was a single table of values of \(\Phi(z)\): \[ P(a \leq Z \leq b) = \Phi(b) - \Phi(a) \,. \] One can argue that standardization is useful for mental calculation: for instance, mentally computing an approximate value for \(P(6 < X < 12)\) when \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(9,9)\) can be quite a bit more taxing than if we were to work with the equivalent expression \(P(-1 < Z < 1)\), which a skilled practitioner would know right away to be \(\approx\) 0.68.

| \((a,b)\) | \(\pm\) 1 | \(\pm\) 2 | \(\pm\) 3 | \(\pm\) 1.645 | \(\pm\) 1.960 | \(\pm\) 2.576 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(P(a \leq Z \leq b)\) | 0.6837 | 0.9544 | 0.9973 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

2.5.1 Computing Probabilities

Here we will reexamine the three examples that we worked through above in the section in which we introduce the normal cumulative distribution function; here, we will utilize standardization. Note: the final results will all be the same!

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(10,4)\), what is \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5)\)?

We standardize \(X\): \(Z = (X-\mu)/\sigma = (X-10)/2\). Hence the bounds of integration are \((8-10)/2 = -1\) and \((13.5-10)/2 = 1.75\), and the probability we seek is \[ P(-1 \leq Z \leq 1.75) = \Phi(1.75) - \Phi(-1) \,. \] To compute the final number, we utilize

pnorm()with its default values ofmean=0andsd=1:

## [1] 0.8012856The probability is 0.801.

- If \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(13,5)\), what is \(P(8 \leq X \leq 13.5 \vert X < 14)\)?

The integral bounds are \((8-13)/\sqrt{5} = -\sqrt{5}\) and \((13.5-13)/\sqrt{5} = \sqrt{5}/10\) in the numerator, and \(-\infty\) and \((14-13/\sqrt{5} = \sqrt{5}/5\) in the denominator. In

R:

## [1] 0.8560226The probability is 0.856.

- If \(\mu = 20\) and \(\sigma^2 = 3\), what is the value of \(a\) such that \(P(20-a \leq X \leq 20+a) = 0.48\)?

Here, \[ P(20-a \leq X \leq 20+a) = P\left( \frac{20-a-20}{\sqrt{3}} \leq \frac{X - 20}{\sqrt{3}} \leq \frac{20+a-20}{\sqrt{3}}\right) = P\left(-\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}} \leq Z \leq \frac{a}{\sqrt{3}} \right) \,, \] and we utilize the symmetry of the standard normal around zero to write \[ P\left(-\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}} \leq Z \leq \frac{a}{\sqrt{3}} \right) = 1 - 2P\left(Z \leq -\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}}\right) = 1 - 2\Phi\left(-\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}}\right) \,. \] Thus \[ 1 - 2\Phi\left(-\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}}\right) = 0.48 ~\Rightarrow~ \Phi\left(-\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}}\right) = 0.26 ~\Rightarrow~ -\frac{a}{\sqrt{3}} = \Phi^{-1}(0.26) = -0.64 \,, \] and thus \(a = 1.114\). (Note that we numerically evaluate \(\Phi^{-1}(0.26)\) using

qnorm(0.26)).

2.6 The Central Limit Theorem

Thus far in this chapter, we have assumed that we have sampled individual data from normal distributions. While we have been able to illustrate many concepts related to probability and statistical inference in this setting, the reader may feel that this is unduly limiting: what if the data we sample are not normally distributed? While we do examine the world beyond normality in future chapters, there is one major concept we can discuss now: the idea that statistics computed using non-normal data can themselves have sampling distributions that are at least approximately normal. This is big: it means that, e.g., we can utilize the same machinery for deriving normal-based confidence intervals and for conducting normal-based hypothesis tests, machinery that we outline below, to generate inferences for these (approximately) normally distributed statistics.

The central limit theorem, or CLT, is one of the most important probability theorems, if not the most important. It states that if we have \(n\) iid random variables \(\{X_1,\ldots,X_n\}\) with mean \(E[X_i] = \mu\) and finite variance \(V[X_i] = \sigma^2 < \infty\), and if \(n\) is sufficiently large, then \(\bar{X}\) is approximately normally distributed, and \((\bar{X}-\mu)/(\sigma/\sqrt{n})\) is approximately standard normally distributed: \[ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} P\left(\frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \leq z \right) = \Phi(z) \,. \] In other words, \[ {\bar X} \stackrel{d}{\rightarrow} Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mu,\frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right) ~~\mbox{or}~~ \frac{\sqrt{n}(\bar{X}-\mu)}{\sigma} \stackrel{d}{\rightarrow} Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \,. \] The limit notation to the left above is to be read as “\(\bar{X}\) converges in distribution to normally distributed random variable,” i.e., the shape of the probability density function for \(\bar{X}\) tends to that of a normal distribution as \(n \rightarrow \infty\). Note that as an alternative to the sample mean, we can also work with the sample sum: \[ X_+ = \sum_{i=1}^n X_i \stackrel{d}{\rightarrow} Y \sim \mathcal{N}\left(n\mu,n\sigma^2\right) ~~\mbox{or}~~ \frac{(X_+-n\mu)}{\sqrt{n}\sigma} \stackrel{d}{\rightarrow} Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \,. \] A proof of the CLT that utilizes moment-generating functions is given in Chapter 7.

Above we added the caveat “if \(n\) is sufficiently large.” How large is sufficiently large? The historical rule of thumb is that if \(n \gtrsim 30\), then we may utilize the CLT. However, the true answer is that it depends on the distribution from which the data are sampled, and thus that it never hurts to perform simulations to see if, e.g., fewer (or more!) data are needed in a particular setting.

Now, there is an apparent limitation of the CLT. We say that \[ \frac{\sqrt{n}(\bar{X}-\mu)}{\sigma} \stackrel{d}{\rightarrow} Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \,, \] but in reality we rarely, if ever, know \(\sigma\). If we use the sample standard deviation \(S\) instead, can we still utilize the CLT? The answer is yes…effectively, it does not change the sample size rule of thumb, but it does mean that we will need a few more samples to achieve the same level of inferential accuracy that we would achieve if we know \(\sigma\). Refer to the proof in Chapter 7. We see that initially, we standardize the random variables (i.e., transform \(X\) to \(Z = (X-\mu)/\sigma\)) and declare that \(E[Z] = 0\) and \(V[Z] = 1\). The latter equality no longer holds if we use \(Z' = (X-\mu)/S\) instead! But \(V[Z']\) does converge to 1 as \(n \rightarrow \infty\): \(S^2 \rightarrow \sigma^2\) by the Law of Large Numbers, and \(S \rightarrow \sigma\) by the continuous mapping theorem. So even if we do not know \(\sigma\), the CLT will “kick in” eventually.

An important final note: if we have data drawn from a known, non-normal distribution and we need to derive the distribution of \(\bar{X}\) in order to, e.g., construct confidence intervals or to perform hypothesis tests, we should not just default to utilizing the CLT! One should only fall back upon the CLT when one cannot determine the exact sampling distribution for \(\bar{X}\), via, e.g., the method of moment-generating functions.

2.6.1 Computing Probabilities

Let’s assume that we have a sample of \(n = 64\) iid data drawn from unknown distribution with mean \(\mu = 10\) and finite variance \(\sigma^2 = 9\). What is the probability that the observed sample mean will be larger than 11?

This is a good example of a canonical CLT exercise: \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) are given to us, but the distribution is left unstated…and \(n \geq 30\). This is a very unrealistic: when will we know population parameters exactly? But such an exercise has its place: it allows us to practice the computation of probabilities. \[\begin{align*} P\left( \bar{X} > 11 \right) &= 1 - P\left( \bar{X} \leq 11 \right) \\ &= 1 - P\left( \frac{\sqrt{n}(\bar{X}-\mu)}{\sigma} \leq \frac{\sqrt{n}(11-\mu)}{\sigma}\right) \\ &\approx 1 - P\left( Z \leq \frac{8(11-10)}{3} \right) = 1 - \Phi\left(\frac{8}{3}\right) \,. \end{align*}\] As we know by now, we cannot go any further by hand, so we call upon

R:

## [1] 0.003830381The probability that \(\bar{X}\) is greater than 11 is small: 0.0038.

To reiterate a point made above: if we were given \(\mu\) but not \(\sigma^2\), we would plug in \(S\) instead and expect that the distribution of \(\sqrt{n}(\bar{X}-\mu)/S\) would be not as close to a standard normal as the distribution of \(\sqrt{n}(\bar{X}-\mu)/\sigma\)…it takes \(\sqrt{n}(\bar{X}-\mu)/S\) “longer” to converge in distribution to a standard normal as \(n\) increases.

2.7 Transformation of a Single Random Variable

Thus far, when discussing transformations of a random variable, we have limited ourselves to linear transformations of independent r.v.’s, i.e., \(Y = b + \sum_{i=1}^n a_i X_i\). What if instead we want to make a more general transformation of a single random variable, e.g., \(Y = X^2 + 3\) or \(Y = \sin X\)? We cannot use the method of moment-generating functions here…we need something new.

Let’s assume we have a continuous random variable \(X\), and we transform it according to a function \(g(\cdot)\): \(U = g(X)\). (Below, in an example, we will show how one would work with discrete random variables.) Furthermore, let’s assume that over the domain of \(X\), the transformation \(U = g(X)\) is one-to-one (or injective). After recalling that a continuous distribution’s pdf is the derivative of its cdf, we can write down the following recipe:

- we identify the inverse function \(X = g^{-1}(U)\);

- we derive the cdf of \(U\): \(F_U(u) = P(U \leq u) = P(g(X) \leq u) = P(X \leq g^{-1}(u))\); and last

- we derive the pdf of \(U\): \(f_U(u) = dF_U(u)/du\).

Because we are assuming that \(U = g(X)\) is a one-to-one function, the domain for \(U\) is found by simply plugging the endpoints of \(X\)’s domain into \(U = g(X)\).

But…what if \(U = g(X)\) is not a one-to-one function? (For example, perhaps \(U = X^2\), and the domain of \(X\) is \([-1,1]\).) If this is the case, then in step (2) above, \(P(g(X) \leq u) \neq P(X \leq g^{-1}(u))\), and the domain cannot be determined by simply using the end-points of the domain of \(X\). In an example below, we show how we use the properties of \(U = g(X)\) to amend the recipe above and get to the right distribution for \(U\) in the end.

We note for completeness that it is possible to make multivariate transformations in which \(U = g(X_1,\ldots,X_p)\), but showing how to perform these is beyond the scope of this book. (The interested reader should consult, e.g., Hogg, McKean, and Craig 2021.)

2.7.1 Continuous Transformation: Injective Function

We are given the following pdf: \[ f_X(x) = 3x^2 \,, \] where \(x \in [0,1]\).

- What is the distribution of \(U = X/3\)?

We follow the three steps outlined above. First, we note that \(U = X/3\) and thus \(X = 3U\). Next, we find \[ F_U(u) = P(U \leq u) = P\left(\frac{X}{3} \leq u\right) = P(X \leq 3u) = \int_0^{3u} 3x^2 dx = \left. x^3 \right|_0^{3u} = 27u^3 \,, \] for \(u \in [0,1/3]\). (The bounds are determined by plugging \(x=0\) and \(x=1\) into \(u = x/3\).) Now we can derive the pdf for \(U\): \[ f_U(u) = \frac{d}{du} 27u^3 = 54u^2 \,, \] for \(u \in [0,1/3]\).

- What is the distribution of \(U = -X\)?

We note that \(U = -X\) and thus \(X = -U\). Next, we find \[ F_U(u) = P(U \leq u) = P(-X \leq u) = P(X \geq -u) = \int_{-u}^{1} 3x^2 dx = \left. x^3 \right|_{-u}^{1} = 1 - (-u)^3 = 1 + u^3 \,, \] for \(u \in [-1,0]\). (Note that the direction of the inequality changed in the probability statement because of the sign change from \(-X\) to \(X\), and the bounds are reversed to be in ascending order.) Now we derive the pdf: \[ f_U(u) = \frac{d}{du} (1+u^3) = 3u^2 \,, \] for \(u \in [-1,0]\).

- What is the distribution of \(U = 2e^X\)?

We note that \(U = 2e^X\) and thus \(X = \log(U/2)\). Next, we find \[\begin{align*} F_U(u) = P(U \leq u) &= P\left(2e^X \leq u\right) = P\left(X \leq \log\frac{u}{2}\right)\\ &= \int_0^{\log(u/2)} 3x^2 dx = \left. x^3 \right|_0^{\log(u/2)} = \left(\log\frac{u}{2}\right)^3 \,, \end{align*}\] for \(u \in [2,2e]\). The pdf for \(U\) is thus \[ f_U(u) = \frac{d}{du} \left(\log\frac{u}{2}\right)^3 = 3\left(\log\frac{u}{2}\right)^2 \frac{1}{u} \,, \] for \(u \in [2,2e]\). Hint: if we want to see if our derived distribution is correct, we can code the pdf in

Rand integrate over the inferred domain.

## [1] 1Our answer is 1, as it should be for a properly defined pdf.

2.7.2 Continuous Transformation: Non-Injective Function

We are given the following pdf: \[ f_X(x) = \frac12 \,, \] where \(x \in [-1,1]\). What is the distribution of \(U = X^2\)?

We begin our calculation as we did above: \[ F_U(u) = P(U \leq u) = P\left(X^2 \leq u\right) = \cdots \,. \] At the last equality, we have to take into account that because \(x\) could be positive or negative, we would not write \(P(X \leq \sqrt{u})\), but rather \(P(-\sqrt{u} \leq X \leq \sqrt{u})\). We can illustrate why this is so in Figure 2.7, which also shows how in the end we determine the domain of \(f_U(u)\).

![\label{fig:noninj}Illustration of the transformation $U = X^2$, where the domain of $f_X(x)$ is $[-1,1]$. The plot immediately indicates the domain of $f_U(u)$: [0,1]. To determine the functional form of $f_U(u)$, we note that for any chosen value of $u$ (here, 0.25), the range of values of $X$ that map to $U < u = x^2$ are the ones bounded by the two vertical red lines (here, $\pm 0.5$). Hence $P(X^2 \leq u) = P(-\sqrt{u} \leq X \leq \sqrt{u})$.](_main_files/figure-html/noninj-1.png)

Figure 2.7: Illustration of the transformation \(U = X^2\), where the domain of \(f_X(x)\) is \([-1,1]\). The plot immediately indicates the domain of \(f_U(u)\): [0,1]. To determine the functional form of \(f_U(u)\), we note that for any chosen value of \(u\) (here, 0.25), the range of values of \(X\) that map to \(U < u = x^2\) are the ones bounded by the two vertical red lines (here, \(\pm 0.5\)). Hence \(P(X^2 \leq u) = P(-\sqrt{u} \leq X \leq \sqrt{u})\).

Continuing on: \[ F_U(u) = P(-\sqrt{u} \leq X \leq \sqrt{u}) = \int_{-\sqrt{u}}^{\sqrt{u}} \frac12 dx = \left. \frac{x}{2} \right|_{-\sqrt{u}}^{\sqrt{u}} = \sqrt{u} \,, \] and \[ f_U(u) = \frac{d}{du} \sqrt{u} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{u}} ~~~ u \in [0,1] \,. \]

2.7.3 Discrete Transformation

Let’s assume that the probability mass function for a random variable \(X\) is \[ p_X(x) = p^x (1-p)^{1-x} \,, \] where \(x \in \{0,1\}\) and \(p \in [0,1]\). Given the transformation \(U = 2X^2\), what is the pmf for \(U\)?

Because the transformation is injective, the determination of the pmf is particularly simple and can be done without carrying out the full set of steps above: we identify that \(X = \sqrt{U/2}\) and state that \[ p_U(u) = p_X\left(\sqrt{\frac{u}{2}}\right) = p^{\sqrt{u/2}} (1-p)^{1-\sqrt{u/2}} \,. \] Since \(x \in \{0,1\}\), the domain of \(u\) is \(\{2 \cdot 0^2,2 \cdot 1^2\}\), or \(\{0,2\}\).

Now, what if instead of the pmf above (which is that of the Bernoulli distribution), we have this pmf instead: \[ p_X(-1) = \frac12 ~~~ \mbox{and} ~~~ p_X(1) = \frac12 \,? \] This is the pmf for the Rademacher distribution. Because \(U = 2X^2\) is not an injective function here, we must take care to establish the mapping of all values in the domain of \(f_X(x)\) to the domain of \(f_U(u)\): \[ X = -1 ~~~\Rightarrow~~~ U = 2 ~~~~~~\mbox{and}~~~~~~ X = 1 ~~~\Rightarrow~~~ U = 2 \,. \] Hence \[ p_U(u) = p_X(-1) + p_X(1) = \frac12 + \frac12 = 1 ~~~ u \in \{2\} \,. \]

2.8 Normal-Related Distribution: Chi-Square

The square of a standard normal random variable, \(Z^2\), is an important quantity that arises, e.g., in statistical model assessment (through the “sum of squared errors” when the “error” is normally distributed) and in hypothesis tests like the chi-square goodness-of-fit test. But for this quantity to be useful in statistical inference, we need to know its distribution.

In step (1) of the algorithm laid out in the last section, we identify the inverse function: if \(U = Z^2\), with \(Z \in (-\infty,\infty)\), then \(Z = \pm \sqrt{U}\). Then, following step (2), we state that \[ F_U(u) = P(U \leq u) = P(Z^2 \leq u) = P(-\sqrt{u} \leq Z \leq \sqrt{u}) = \Phi(\sqrt{u}) - \Phi(-\sqrt{u}) \,, \] where, as we recall, \(\Phi(\cdot)\) is the notation for the standard normal cdf. Because of symmetry, we can simplify this expression: \[ F_U(u) = \Phi(\sqrt{u}) - [1 - \Phi(\sqrt{u})] = 2\Phi(\sqrt{u}) - 1 \,. \]

To carry out step (3), we utilize the chain rule of differentiation to determine that the pdf is \[\begin{align*} f_U(u) = \frac{d}{du} F_U(u) = \frac{d}{du} [2\Phi(\sqrt{u}) - 1] &= 2 \frac{d\Phi}{du}(\sqrt{u}) \cdot \frac{d}{du}\sqrt{u} \\ &= 2 f_Z(\sqrt{u}) \cdot \frac{1}{2\sqrt{u}} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{u}{2}\right) \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{u}} \\ &= \frac{u^{-1/2}}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp(-\frac{u}{2}) \,, \end{align*}\] with \(u \in [0,\infty)\).

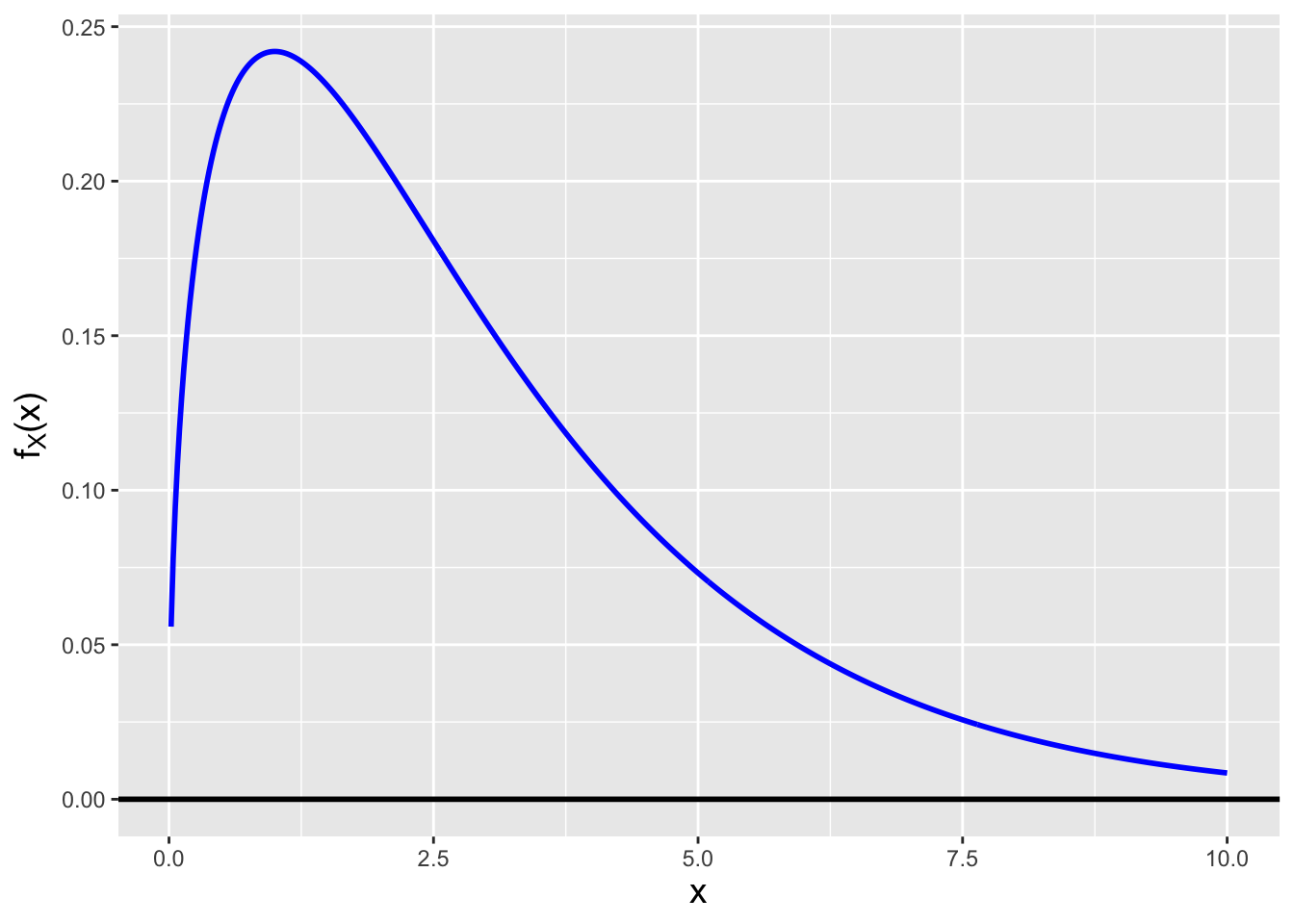

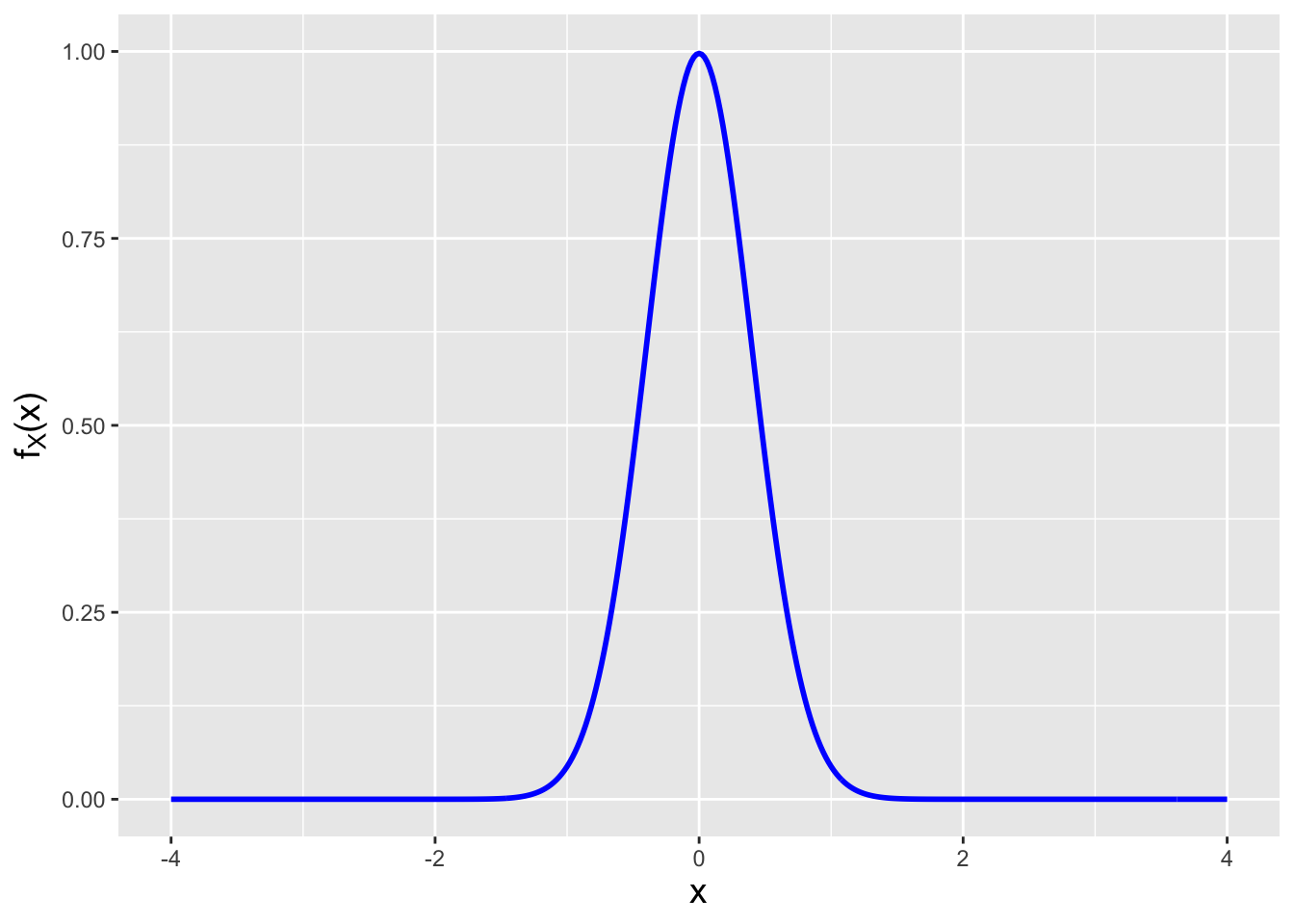

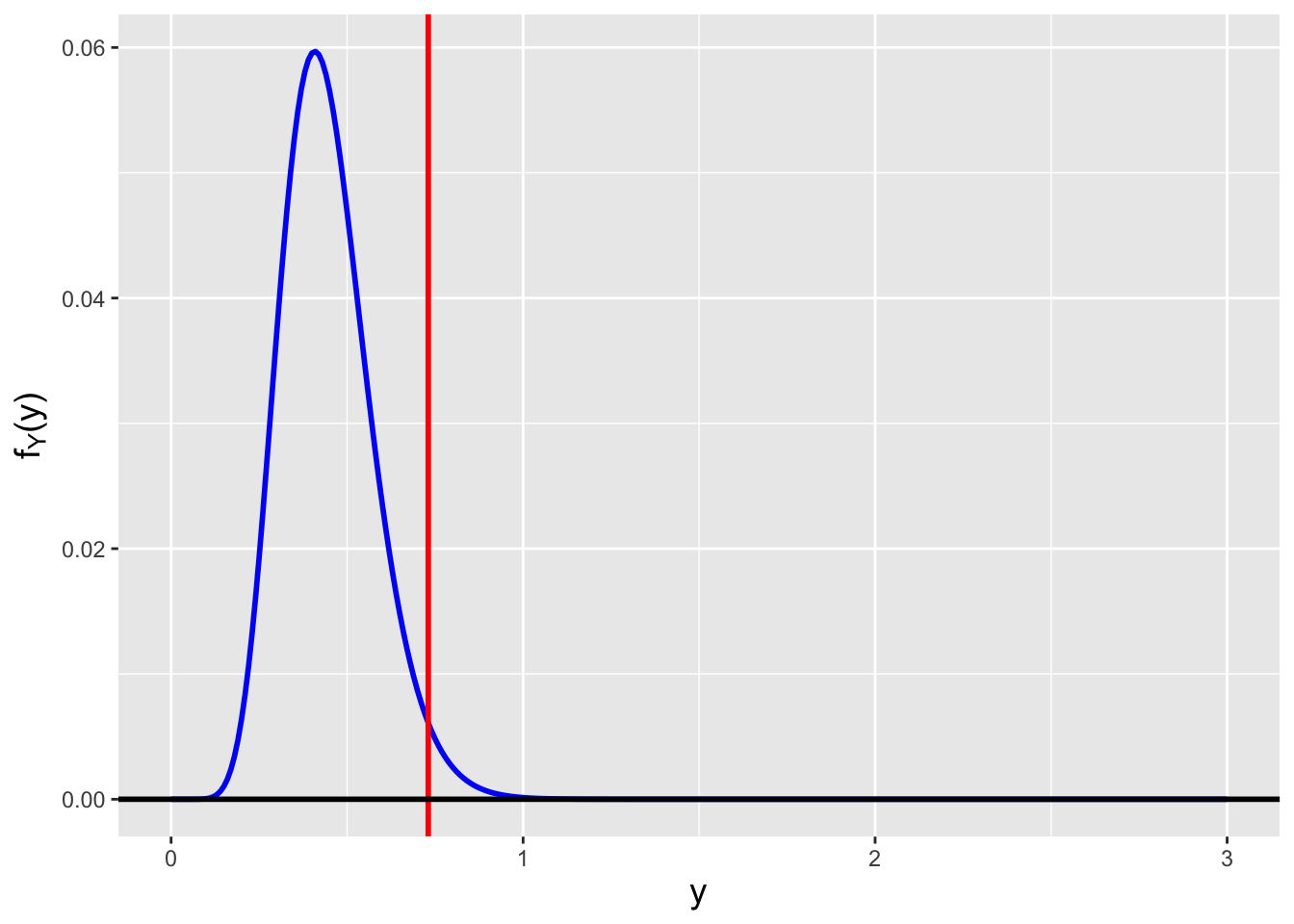

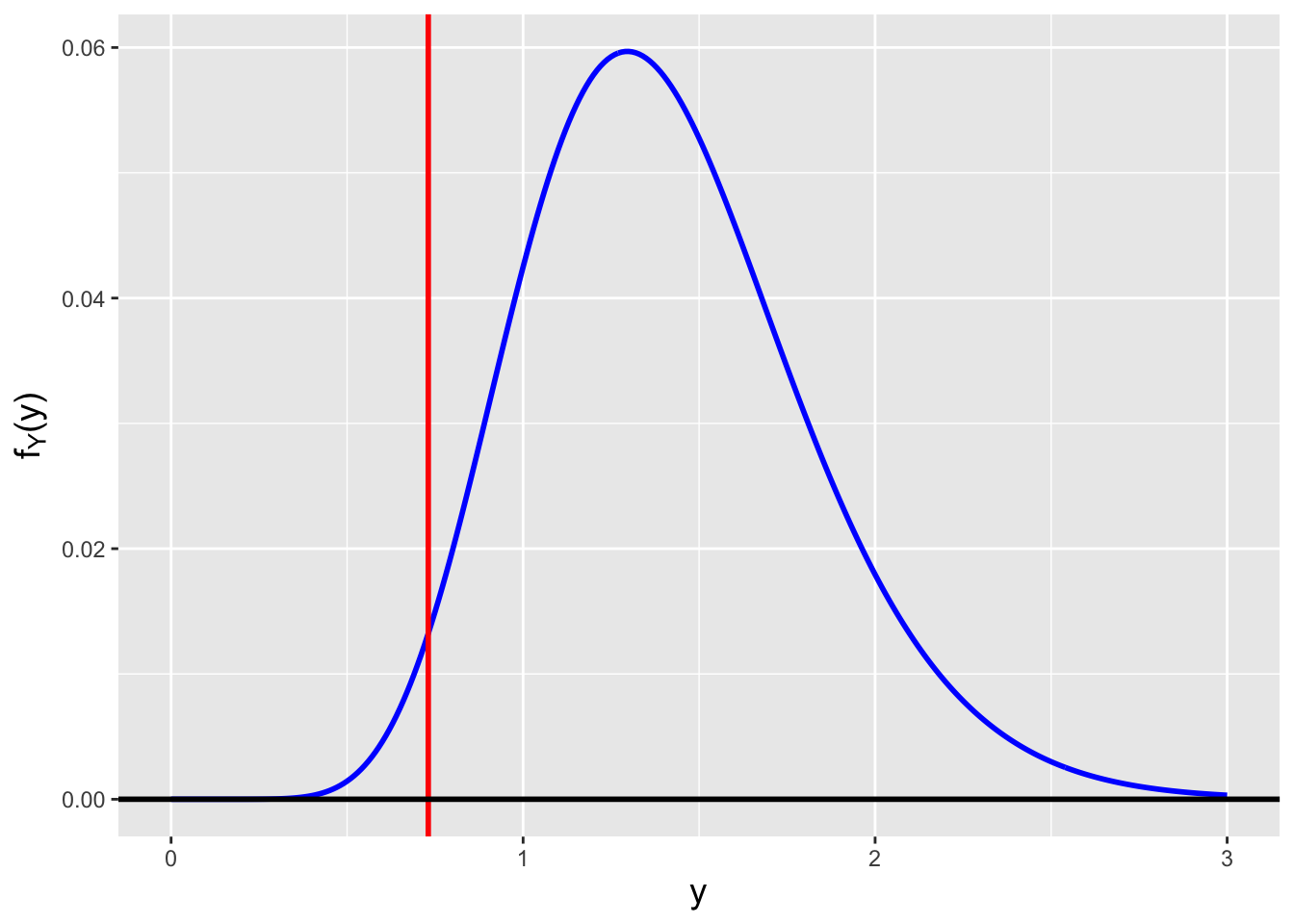

Before continuing, we need to introduce a new probability distribution, the so-called chi-square distribution, which has the probability density function \[ f_W(x) = \frac{x^{\nu/2-1}}{2^{\nu/2} \Gamma(\nu/2)} \exp\left(-\frac{x}{2}\right) \,, \] where \(x \geq 0\) and \(\nu\) is a positive integer; \(E[X] = \nu\) and \(V[X] = 2\nu\). Note that we will use the notation \(W\) to denote a chi-square random variable throughout the remainder of this book. The one parameter that dictates the shape of a chi-square distribution is dubbed the number of degrees of freedom, is conventionally denoted with the Greek letter \(\nu\) (nu, pronounced “noo”), and has a positive integer value. A chi-square distribution is highly skew if \(\nu\) is small, but chi-square random variables converge in distribution to normal random variables as \(\nu \rightarrow \infty\). See Figure 2.8. (As we will see in Chapter 4, the chi-square family of distributions belongs to the more general gamma family of distributions.)

Figure 2.8: Chi-square distributions for \(\nu = 3\) (left) and \(\nu = 30\) (right) degrees of freedom. Chi-square random variables converge in distribution to normal random variables as \(\nu \rightarrow \infty\).

Now let’s go back to the result of our transformation. We can now see that \(f_U(u)\) is a chi-square pdf: \[ U = W \sim \chi_1^2 \,, \] with the subscript “1” indicating that here, \(\nu = 1\).

So: if we take a single standard normal random variable \(Z\) and square it, the squared value is sampled according to a chi-square distribution for one degree of freedom. What if now we were to generate a sample of \(n\) independent standard-normal random variables \(\{Z_1,\ldots,Z_n\}\)…what is the distribution of \(\sum_{i=1}^n Z_i^2\)? As this is a sum of independent random variables, we utilize the method of moment-generating functions to answer this question. As shown in the first example below, the mgf for a chi-square random variable is \[ m_W(t) = (1-2t)^{-\nu/2} \,. \] The mgf of a sum of chi-square random variables, each of which has \(\nu = 1\) degrees of freedom, will be \[ \prod_{i=1}^n m_{W}(t) = \prod_{i=1}^n (1-2t)^{-\frac{1}{2}} = (1-2t)^{-\frac{n}{2}} \,. \] We identify the product as being the mgf for a chi-square distribution with \(\nu = n\) degrees of freedom. Thus: if we sum chi-square-distributed random variables, the summed quantity is itself chi-square distributed, with \(\nu\) being the sum of the numbers of degrees of freedom for the original random variables. (This result can be generalized: for instance, if \(X_1 \sim \chi_a^2\) and \(X_2 \sim \chi_b^2\), then \(X_1 + X_2 = W \sim \chi_{a+b}^2\).)

2.8.1 Chi-Square Distribution: Moment-Generating Function

The moment-generating function for a chi-square random variable is \[ E[e^{tX}] = \int_0^\infty e^{tx} \frac{x^{\nu/2-1}}{2^{\nu/2} \Gamma(\nu/2)} e^{-x/2} dx = \int_0^\infty \frac{x^{\nu/2-1}}{2^{\nu/2} \Gamma(\nu/2)} e^{-(1/2-t)x} dx \,. \] Because the integral bounds are \(0\) and \(\infty\), we utilize a variable transformation that yields an integrand containing \(e^{-u}\); we can then evaluate the integral as a gamma function. Thus \(u = (1/2-t)x\) and \(du = (1/2-t)dx\), with the integral bounds being unchanged, and we have that \[\begin{align*} E[e^{tX}] &= \int_0^\infty \frac{[u/(1/2-t)]^{\nu/2-1}}{2^{\nu/2} \Gamma(\nu/2)} e^{-u} \frac{du}{1/2-t} \\ &= \frac{1}{(1/2-t)^{\nu/2}} \frac{1}{2^{\nu/2}} \frac{1}{\Gamma(\nu/2)} \int_0^\infty u^{\nu/2-1} e^{-u} du \\ &= \frac{1}{(1-2t)^{\nu/2}} \frac{1}{\Gamma(\nu/2)} \Gamma(\nu/2) = (1-2t)^{-\nu/2} \,. \end{align*}\]

2.8.2 Chi-Square Distribution: Expected Value

The expected value of a chi-square distribution for one degree of freedom is \[\begin{align*} E[X] &= \int_0^\infty x f_X(x) dx \\ &= \int_0^\infty \frac{x^{1/2}}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\exp\left(-\frac{x}{2}\right) dx \,. \end{align*}\] To find the value of this integral, we are going to utilize the gamma function \[ \Gamma(t) = \int_0^\infty u^{t-1} \exp(-u) du \,, \] which we first introduced in Chapter 1. (Note that \(t > 0\).) Recall that if \(t\) is an integer, then \(\Gamma(t) = (t-1)! = (t-1) \times (t-2) \times \cdots \times 1\), with the exclamation point representing the factorial function. If \(t\) is a half-integer and small, one can look up the value of \(\Gamma(t)\) online.

The integral we are trying to compute doesn’t quite match the form of the gamma function integral…but as one should recognize by now, we can attempt a variable substitution to change \(e^{-x/2}\) to \(e^{-u}\): \[ u = x/2 ~,~ du = dx/2 ~,~ x = 0 \implies u = 0 ~,~ x = \infty \implies u = \infty \] We thus rewrite our expected value as \[\begin{align*} E[X] &= \int_0^\infty \frac{\sqrt{2}u^{1/2}}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp(-u) (2 du) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^\infty u^{1/2} \exp(-u) du \\ &= \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} = 1 \,. \end{align*}\] As we saw above, the sum of \(n\) chi-square random variables, each distributed with 1 degree of freedom, is itself chi-square-distributed for \(n\) degrees of freedom. Hence, in general, if \(W \sim \chi_{n}^2\), then \(E[W] = n\).

2.8.3 Computing Probabilities

Let’s assume at first that we have a single random variable \(Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\).

- What is \(P(Z^2 > 1)\)?

We know that \(Z^2\) is sampled according to a chi-square distribution for 1 degree of freedom. So \[ P(Z^2 > 1) = 1 - P(Z^2 \leq 1) = 1 - F_{W(1)}(1) \,. \] This is not easily computed by hand, so we utilize

R:

## [1] 0.3173105The probability is 0.3173. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see why this was going to be the value all along: we know that \(P(-1 \leq Z \leq 1) = 0.6827\), and thus \(P(\vert Z \vert > 1) = 1-0.6827 = 0.3173\). If we square both sides in this last probability statement, we see that \(P(\vert Z \vert > 1) = P(Z^2 > 1)\).

- What is the value \(a\) such that \(P(W > a) = 0.9\), where \(W = Z_1^2 + \cdots + Z_4^2\) and \(\{Z_1,\ldots,Z_4\}\) are iid standard normal random variables?

First, we recognize that \(W \sim \chi_4^2\), i.e., \(W\) is chi-square distributed for 4 degrees of freedom.

Second, we re-express \(P(W > a)\) in terms of the cdf of the chi-square distribution, \[ P(W > a) = 1 - P(W \leq a) = 1 - F_{W(4)}(a) = 0.9 \,, \] and we rearrange terms: \[ F_{W(4)}(a) = 0.1 \,. \] To isolate \(a\), we use the inverse CDF function: \[ F_{W(4)}^{-1} [F_{W(4)}(a)] = a = F_{W(4)}^{-1}(0.1) \,. \] To compute \(a\), we use the

Rfunctionqchisq():

## [1] 1.063623We find that \(a = 1.064\).

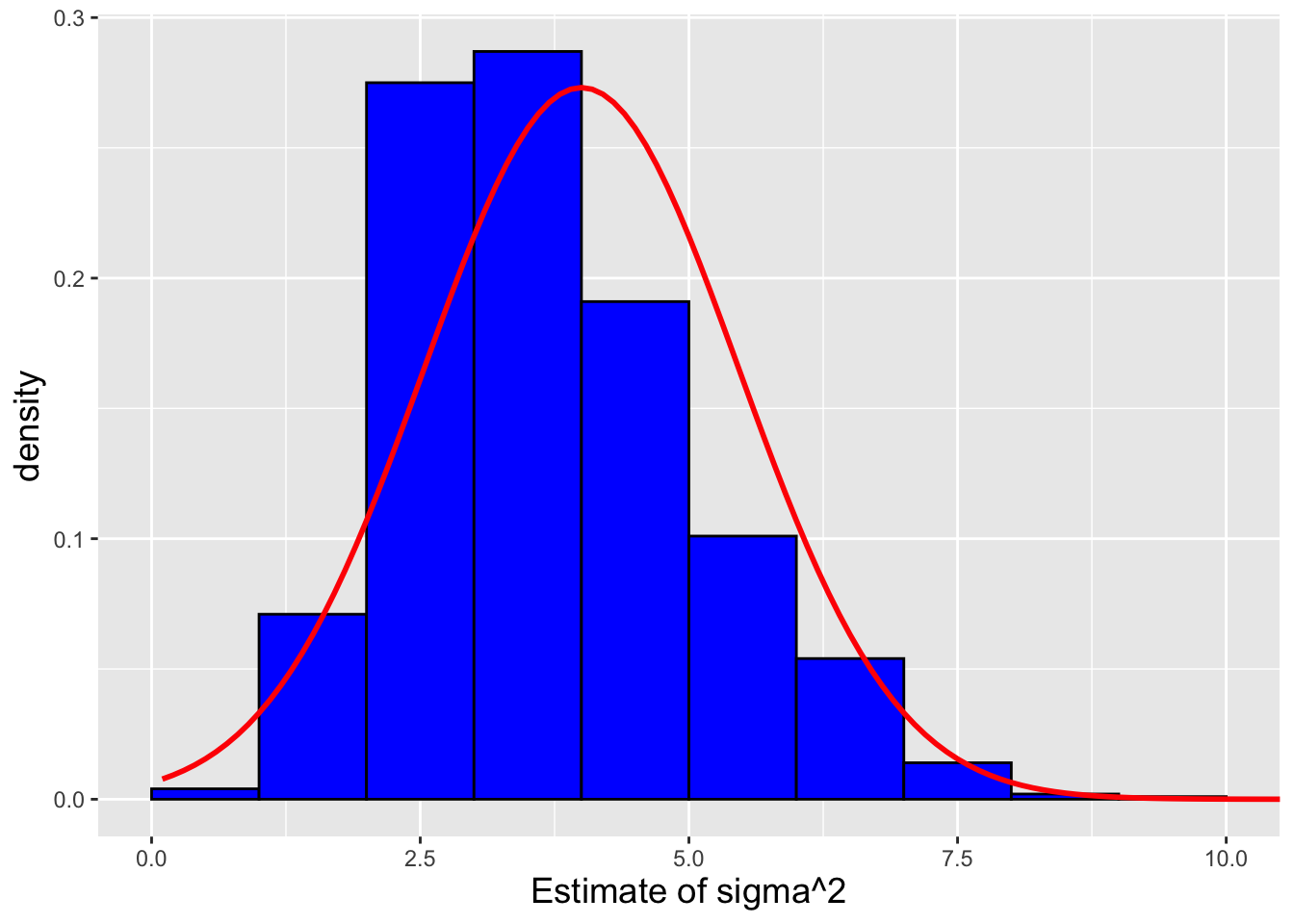

2.9 Normal Distribution: Sample Variance

Recall the definition of the sample variance: \[ S^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X})^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \left[ \left( \sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2 \right) - n\bar{X}^2 \right] \,. \] The reason why we divide by \(n-1\) instead of \(n\) is that it makes \(S^2\) an unbiased estimator of \(\sigma^2\). We will illustrate this point below when we cover point estimation.

Previously, we showed how the sample mean of iid normal random variables is itself normal, with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2/n\). What, on the other hand, is the distribution of \(S^2\)?

We could try to derive this directly, by utilizing transformations and the method of moment-generating functions, but we would run into the issue that, e.g., \(\sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2\) and \(\bar{X}^2\) are not independent random variables. So we will attack this derivation a bit more indirectly instead.

Suppose that we have \(n\) iid normal random variables. We can write down that \[ \sum_{i=1}^n \left( \frac{X_i-\mu}{\sigma} \right)^2 = W \sim \chi_n^2 \,. \] We can work with the expression to the left of the equals sign to determine the distribution of \((n-1)S^2/\sigma^2\): \[\begin{align*} \sum_{i=1}^n \left( \frac{X_i-\mu}{\sigma} \right)^2 &= \sum_{i=1}^n \left( \frac{(X_i-\bar{X})+(\bar{X}-\mu)}{\sigma} \right)^2 \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n \left( \frac{X_i-\bar{X}}{\sigma}\right)^2 + \sum_{i=1}^n \left( \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2 + \mbox{cross~term~equaling~zero} \\ &= \frac{(n-1)S^2}{\sigma^2} + n\left(\frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2 = \frac{(n-1)S^2}{\sigma^2} + \left(\frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}\right)^2 \,. \end{align*}\] The expression farthest to the right contains the quantity \[ \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \,, \] which, since \(\bar{X} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma^2/n)\), is a standard normal random variable. Thus the expression itself represents a chi-square-distributed random variable for 1 dof. Recall that if \(X_1 \sim \chi_a^2\) and \(X_2 \sim \chi_b^2\), then \(X_1 + X_2 \sim \chi_{a+b}^2\); given this, it must be the case that \[ \frac{(n-1)S^2}{\sigma^2} = W' \sim \chi_{n-1}^2 \,. \]

Now we can determine the distribution of \(S^2\), by utilizing the transformation \[ S^2 = \frac{\sigma^2 W'}{n-1} \,. \] We have that \[\begin{align*} F_{S^2}(x) = P(S^2 \leq x) = P\left( \frac{\sigma^2 W'}{n-1} \leq x \right) = P\left( W' \leq \frac{(n-1)x}{\sigma^2} \right) = F_{W'}\left(\frac{(n-1)x}{\sigma^2} \right) \,, \end{align*}\] and thus \[\begin{align*} f_{S^2}(x) &= \frac{d}{dx} F_{S^2}(x) = f_{S^2}\left(\frac{(n-1)x}{\sigma^2} \right) \frac{(n-1)}{\sigma^2} \\ &= \frac{\left[\frac{(n-1)x}{\sigma^2}\right]^{(n-1)/2 - 1}}{2^{(n-1)/2} \Gamma\left((n-1)/2\right)} \exp\left(-\frac{(n-1)x}{2\sigma^2}\right) \frac{(n-1)}{\sigma^2} \,. \end{align*}\] If we let \(a = (n-1)/2\) and \(b = 2\sigma^2/(n-1)\), then the pdf above becomes \[ f_{S^2}(x) = \frac{x^{a-1}}{b^a\Gamma(a)} \exp\left(-\frac{x}{b}\right) \,. \] This is the pdf of a gamma distribution with shape parameter \(a\) and scale parameter \(b\), i.e., \[ S^2 \sim \mbox{Gamma}\left(\frac{n-1}{2},\frac{2\sigma^2}{n-1}\right) \,. \] We discuss the gamma distribution in Chapter 4; for now, it suffices to say that if \(X\) is a gamma-distributed random variable, then \(E[X] = ab\) and \(V[X] = ab^2\)…thus \(E[S^2] = \sigma^2\) and \(V[S^2] = 2\sigma^4/(n-1)\).

2.9.1 Computing Probabilities

Let’s suppose we sample \(16\) iid normal random variables, and we know that \(\sigma^2 = 10\). What is the probability \(P(S^2 > 12)\)?

(We’ll stop for a moment to answer a question that might occur to the reader. “Why are we doing a problem where we assume \(\sigma^2\) is known? In real life, it almost certainly won’t be.” This is an entirely fair question. This example is contrived, but it builds towards a particular situation where we can assume a value for \(\sigma^2\): hypothesis testing. The calculation we do below is analogous to calculations we will do later when testing hypotheses about normal population variances.)

To compute the probability, we write \(P(S^2 > 12) = 1 - P(S^2 \leq 12)\) and utilize the cdf of a gamma distribution:

## [1] 0.26266562.9.2 Expected Value of the Standard Deviation

Above, we determined that when we sample \(n\) iid data according to a normal distribution, the sample variance \(S^2\) is gamma-distributed with shape parameter \(a = (n-1)/2\) and scale parameter \(b = 2\sigma^2/(n-1)\), and the expected value of \(S^2\) is \(\sigma^2\)…meaning that \(S^2\) is an unbiased estimator for population variance \(\sigma^2\).

A natural question which then arises is: is the sample standard deviation \(S\) an unbiased estimator for the population standard deviation \(\sigma\)?

To answer this, we first must determine the probability distribution function \(f_S(x)\). This is straightforwardly done via the transformation \(S = \sqrt{S^2}\): \[ F_S(x) = P(S \leq x) = P(\sqrt{S^2} \leq x) = P(S^2 \leq x^2) = F_{S^2}(x^2) \,, \] and thus \[ f_S(x) = \frac{d}{dx} F_S(x) = 2 x f_{S^2}(x^2) = 2 x \frac{(x^2)^{a-1}}{b^a \Gamma(a)} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{b}\right) \,, \] where \(x > 0\). (Note that this distribution has a name: it is a Nakagami distribution.)

The expected value of \(S\) is \[ E[S] = \int_0^\infty 2 x^2 \frac{(x^2)^{a-1}}{b^a \Gamma(a)} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{b}\right) dx = 2 \left(\frac{x^2}{b}\right)^a \frac{1}{\Gamma(a)} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{b}\right) dx \,. \] Given the integral bounds, we utilize the variable transformation \(t = x^2/b\), such that \(dt = 2 x dx/b\) (with the integral bounds being unchanged). Thus \[\begin{align*} E[S] &= \frac{2}{\Gamma(a)} \int_0^\infty t^a \exp(-t) \frac12 \sqrt{\frac{b}{t}} dt \\ &= \frac{\sqrt{b}}{\Gamma(a)} \int_0^\infty t^{a-1/2} \exp(-t) dt \\ &= \frac{\Gamma(a+1/2)}{\Gamma(a)} \sqrt{b} \\ &= \frac{\Gamma(n/2)}{\Gamma((n-1)/2)} \sqrt{\frac{2}{n-1}} \sigma \neq \sigma \,. \end{align*}\] We thus find that \(S\) is a biased estimator of the normal standard deviation \(\sigma\). We note that \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{\Gamma(n/2)}{\Gamma((n-1)/2)} = \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{\Gamma((n-1)/2 + 1/2)}{\Gamma((n-1)/2)} = \left(\frac{n-1}{2}\right)^{1/2} \,, \] so asymptotically \(S\) is an unbiased estimator for \(\sigma\).

2.10 Normal-Related Distribution: t

It is generally the case in real-life that when we assume our data are sampled according to a normal distribution, both the mean and the variance are unknown. This means that instead of \[ Z = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1) \,, \] we have \[ \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{S/\sqrt{n}} \sim \mbox{?} \] This last expression contains two random variables, one in the numerator and one in the denominator, and each is independent of the other. (We state this without proof…but we will appeal to intuition. For many distributions, the expected value and variance are both functions of one or more parameters \(\theta\) [e.g., the exponential, binomial, and Poisson distributions, etc., etc.]. However, for a normal distribution, the expected value only depends on \(\mu\) and the variance only depends on \(\sigma^2\).) How would we determine the distribution of the ratio above?

There is no unique way by which to approach the derivation of the distribution: we simply illustrate one way of doing so. First, we rewrite the ratio above as \[ T = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{S/\sqrt{n}} = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} / \frac{S}{\sigma} = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} / \sqrt{\frac{S^2}{\sigma^2}} = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} / \left( \sqrt{\frac{\nu S^2}{\sigma^2}} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\nu}} \right) = Z / \left(\sqrt{\frac{W}{\nu}}\right) \,, \] where \(Z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) and \(W\) is sampled according to a chi-square distribution with \(\nu = n-1\) degrees of freedom. Our next step is to determine the distribution of the random variable \(U = \sqrt{W/\nu}\). We identify that \(V = \sqrt{W}\) is sampled according to a chi distribution (note: no square!), whose pdf may be derived via a general transformation (since \(V = \sqrt{\nu}S/\sigma\) and since we have written down \(f_S(x)\) above), but can also simply be looked up: \[ f_V(x) = \frac{x^{\nu-1} \exp(-x^2/2)}{2^{\nu/2-1}\Gamma(\nu/2)} \,, \] for \(x \geq 0\) and \(\nu > 0\). However, we do still have to apply a general transformation to determine the pdf for \(U = V/\sqrt{\nu}\). Doing so, we find that \[ f_U(x) = f_V(\sqrt{\nu}x) \sqrt{\nu} = \frac{\sqrt{\nu} (\sqrt{\nu}x)^{\nu-1} \exp(-(\sqrt{\nu}x)^2/2)}{2^{\nu/2-1}\Gamma(\nu/2)} \,. \] (So, yes, we could have derived \(f_U(x)\) directly from \(f_S(x)\) via a general transformation…but here we at least indicate to the reader that there is such a thing as the chi distribution.)

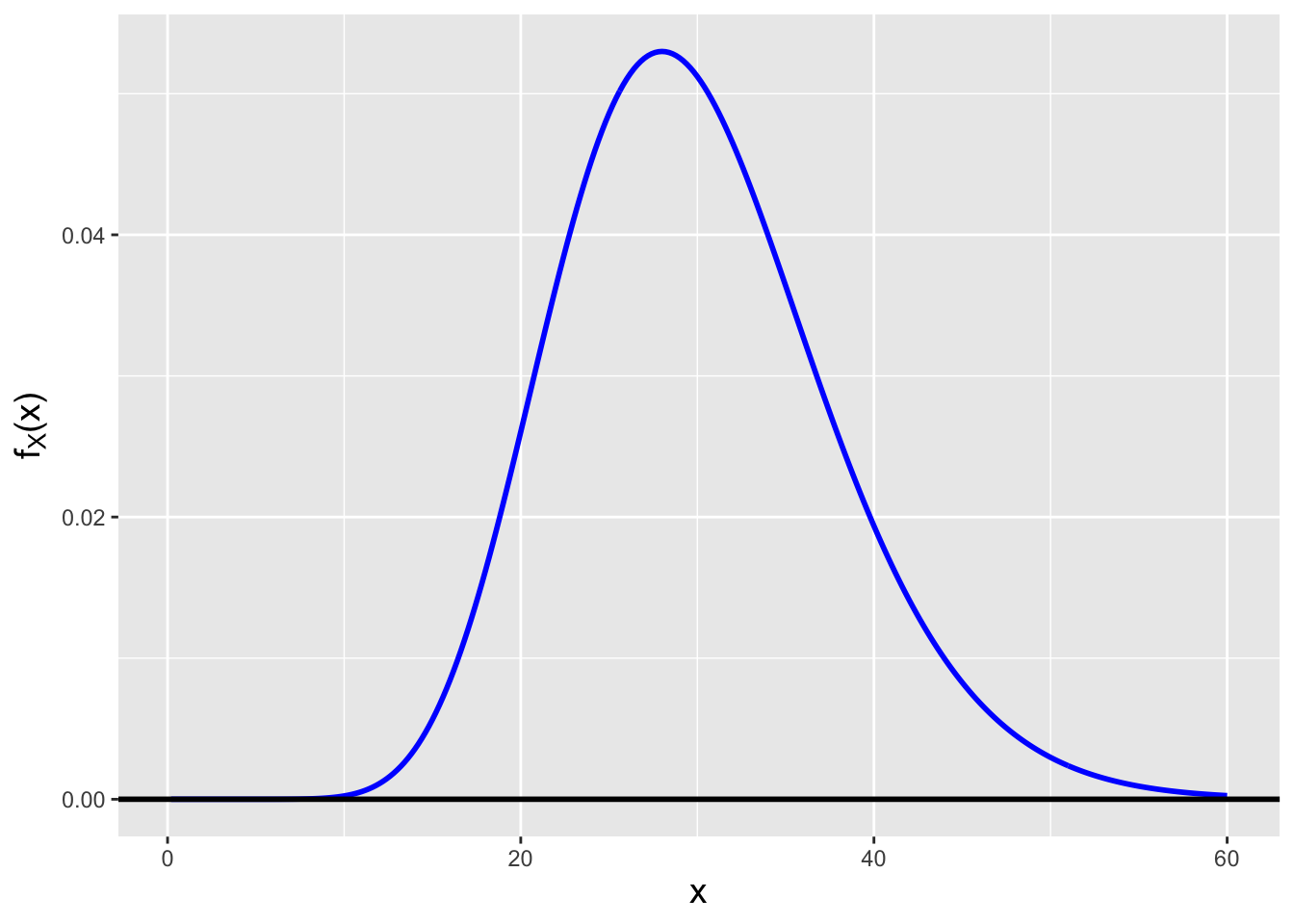

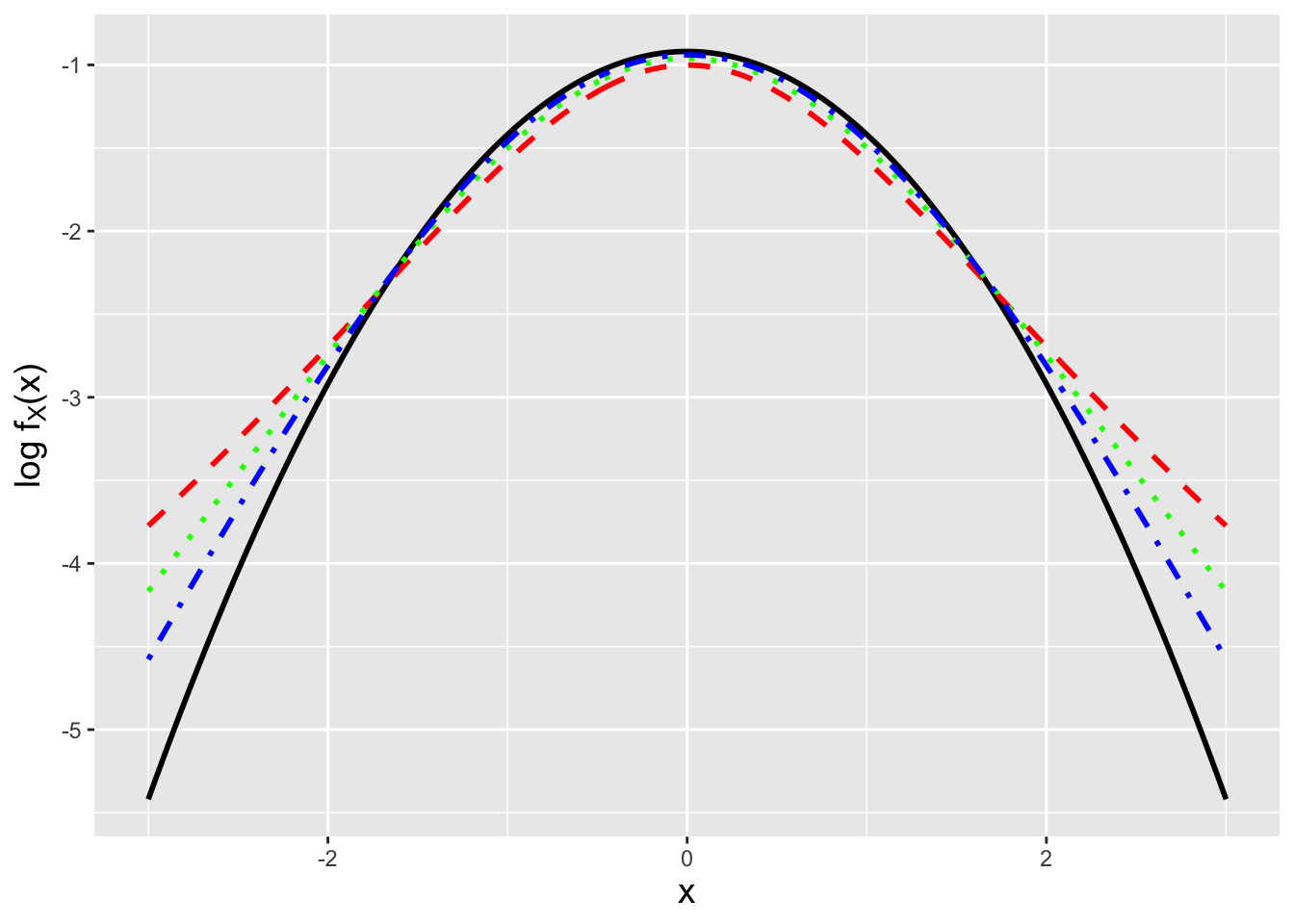

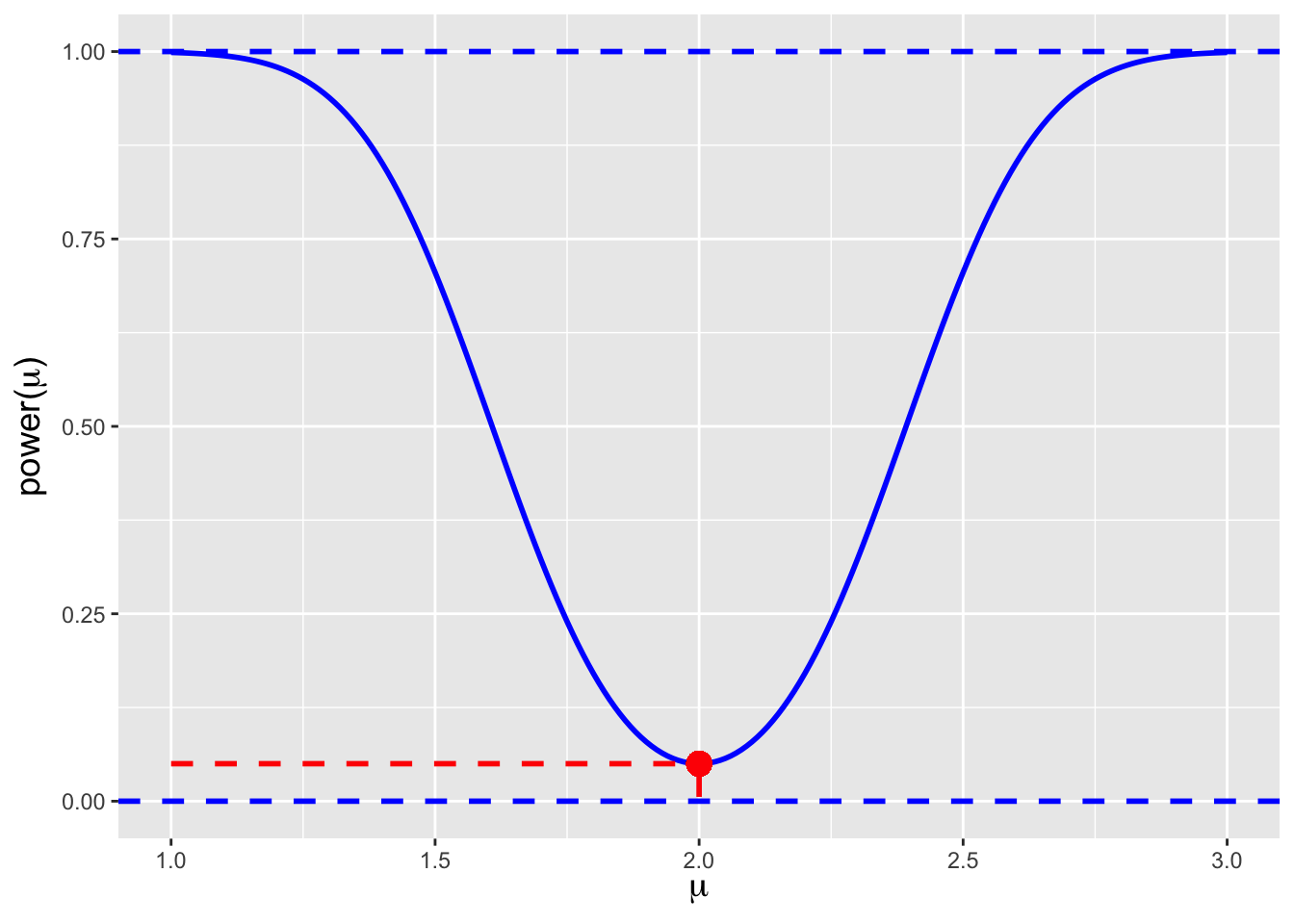

At this point, we know the distributions for both the numerator and the denominator. Now we write down a general result dubbed the ratio distribution. For \(T = Z/U\), where \(Z\) and \(U\) are independent variables, that distribution is \[ f_T(t) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty \vert u \vert f_Z(tu) f_{U}(u) du \rightarrow \int_0^\infty u f_Z(tu) f_{U}(u) du \,, \] where we make use of the fact that \(u > 0\). Thus \[\begin{align*} f_T(t) &= \int_0^\infty u \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{t^2u^2}{2}\right) \frac{\sqrt{\nu} (\sqrt{\nu}u)^{\nu-1} \exp(-(\sqrt{\nu}u)^2/2)}{2^{\nu/2-1}\Gamma(\nu/2)} du \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \frac{1}{2^{\nu/2-1}\Gamma(\nu/2)} \nu^{\nu/2} \int_0^\infty u^\nu \exp\left(-\frac{(t^2+\nu)u^2}{2}\right) du \,. \end{align*}\] Given the form of the integral and the fact that it is evaluated from zero to infinity, we will use a variable substitution approach and eventually turn the integral into a gamma function: \[ x = \frac{(t^2+\nu)u^2}{2} ~~~ \Rightarrow ~~~ dx = (t^2+\nu)~u~du \,. \] When \(u = 0\), \(x = 0\), and when \(u = \infty\), \(x = \infty\), so the integral bounds are unchanged. Hence we can rewrite the integral above as \[\begin{align*} f_T(t) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \frac{1}{2^{\nu/2-1}\Gamma(\nu/2)} \nu^{\nu/2} \int_0^\infty \left(\sqrt{\frac{2x}{(t^2+\nu)}}\right)^\nu \exp\left(-x\right) \frac{dx}{\sqrt{2 x (t^2+\nu)}} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \frac{1}{2^{\nu/2-1}\Gamma(\nu/2)} \nu^{\nu/2} 2^{\nu/2} 2^{-1/2} \frac{1}{(t^2+\nu)^{(\nu+1)/2}} \int_0^\infty \frac{x^{\nu/2}}{x^{1/2}} \exp\left(-x\right) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} \frac{1}{\Gamma(\nu/2)} \nu^{\nu/2} \frac{1}{(t^2+\nu)^{(\nu+1)/2}} \int_0^\infty x^{\nu/2-1/2} \exp\left(-x\right) dx \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} \frac{1}{\Gamma(\nu/2)} \nu^{\nu/2} \frac{1}{(t^2+\nu)^{(\nu+1)/2}} \Gamma((\nu+1)/2) \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} \frac{\Gamma((\nu+1)/2)}{\Gamma(\nu/2)} \nu^{\nu/2} \frac{1}{\nu^{(\nu+1)/2}(t^2/\nu+1)^{(\nu+1)/2}} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{\nu \pi}} \frac{\Gamma((\nu+1)/2)}{\Gamma(\nu/2)} \left(1+\frac{t^2}{\nu}\right)^{-(\nu+1)/2} \,. \end{align*}\] \(T\) is sampled according to a Student’s t distribution for \(\nu\) degrees of freedom. Assuming that \(\nu\) is integer-valued, the expected value of \(T\) is \(E[T] = 0\) for \(\nu \geq 2\) (and is undefined otherwise), while the variance is \(\nu/(\nu-2)\) for \(\nu \geq 3\), is infinite for \(\nu=2\), and is otherwise undefined. Appealing to intuition, we can form a (symmetric) \(t\) distribution by taking a standard normal \(\mathcal{N}(0,1)\) and “pushing down” in the center, the act of which transfers probability density equally to both the lower and upper tails. In Figure 2.9, we see that the smaller the number of degrees of freedom, the more density is transferred to the tails, and that as \(\nu\) increases, the more and more \(f_{T(\nu)}(t)\) becomes indistinguishable from a standard normal. (The more technical way of stating this is that the random variable \(T\) converges in distribution to a standard normal random variable as \(\nu \rightarrow \infty\).)

Figure 2.9: The natural logarithm of the pdf for the standard normal (black) and for \(t\) distributions with 3 (red dashed), 6 (green dotted), and 12 (blue dot-dashed) degrees of freedom. We observe that as \(n\) decreases, there is more probability density in the lower and upper tails of the distributions.

2.10.1 Computing Probabilities

In a study, the diameters of 8 widgets are measured. It is known from previous work that the widget diamaters are normally distributed, with sample standard deviation \(S = 1\) unit. What is the probability that the the sample mean \(\bar{X}\) observed in the current study will be within one unit of the population mean \(\mu\)?

The probability we seek is \[ P( \vert \bar{X} - \mu \vert < 1 ) = P(\mu - 1 \leq \bar{X} \leq \mu + 1) \,. \] The key here is that we don’t know \(\sigma\), so the probability can only be determined if we manipulate this expression such that the random variable inside it is \(t\)-distributed…and \(\bar{X}\) itself is not. So the first step is to standardize: \[ P\left( \frac{\mu - 1 - \mu}{S/\sqrt{n}} \leq \frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{S/\sqrt{n}} \leq \frac{\mu + 1 - \mu}{S/\sqrt{n}}\right) = P\left( -\frac{\sqrt{n}}{S} \leq T \leq \frac{\sqrt{n}}{S}\right) \,. \] We know that \(\sqrt{n}(\bar{X} - \mu)/S\) is \(t\)-distributed (with \(\nu = n-1\) degrees of freedom), so long as the individual data are normal iid random variables. (If the individual data are not normally distributed, this question might have to be solved via simulations…if we cannot determine the distribution of \(\bar{X}\) using, e.g., moment-generating functions.)

The probability is the difference between two cdf values: \[ P\left( -\frac{\sqrt{n}}{S} \leq T \leq \frac{\sqrt{n}}{S}\right) = F_{T(7)}(\sqrt{8}) - F_{T(7)}(-\sqrt{8}) \,, \] where \(n-1\), the number of degrees of freedom, is 7. This is the end of the problem if we are using pen and paper. If we have

Rat our disposal, we would code the following:

## [1] 0.9745364The probability that \(\bar{X}\) will be within one unit of \(\mu\) is 0.975.

2.11 Point Estimation

In the previous chapter, we introduced the concept of point estimation, using statistics to make inferences about a population parameter \(\theta\). Recall that a point estimator \(\hat{\theta}\), being a statistic, is a random variable and has a sampling distribution. One can define point estimators arbitrarily, but in the end, we can choose the best among a set of estimators by assessing properties of their sampling distributions:

- Bias: \(B[\hat{\theta}] = E[\hat{\theta}-\theta]\)

- Variance: \(V[\hat{\theta}]\)

Recall: the bias of an estimator is the difference between the average value of the estimates it generates and the true parameter value. If \(E[\hat{\theta}-\theta] = 0\), then the estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) is said to be unbiased.

Assuming that our observed data are independent and identically distributed (or iid), then computing each of these quantities is straightforward. Choosing a best estimator based on these two quantities might not lead to a clear answer, but we can overcome that obstacle by combining them into one metric, the mean-squared error (or MSE):

- MSE: \(MSE[\hat{\theta}] = B[\hat{\theta}]^2 + V[\hat{\theta}]\)

In the previous chapter, we also discussed how guessing the form of an estimator is sub-optimal, and how there are various approaches to deriving good estimators. The first one that we highlight is maximum likelihood estimation (or MLE). We will apply the MLE here to derive an estimator for the normal population mean. Then we will introduce methodology by which to assess the estimator in an absolute sense, and extend these results to write down the asymptotic sampling distribution for the MLE, i.e., the sampling distribution as the sample size \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

Recall: the value of \(\theta\) that maximizes the likelihood function is the maximum likelihood estimate, or MLE, for \(\theta\). The maximum is found by taking the (partial) derivative of the (log-)likelihood function with respect to \(\theta\), setting the result to zero, and solving for \(\theta\). That solution is the maximum likelihood estimate \(\hat{\theta}_{MLE}\). Also recall the invariance property of the MLE: if \(\hat{\theta}_{MLE}\) is the MLE for \(\theta\), then \(g(\hat{\theta}_{MLE})\) is the MLE for \(g(\theta)\).

The setting, again, is that we have randomly sampled \(n\) data from a normal distribution with parameters \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\). This means that the likelihood function is \[\begin{align*} \mathcal{L}(\mu,\sigma \vert \mathbf{x}) &= \prod_{i=1}^n f_X(x \vert \mu,\sigma) \\ &= \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x_i-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \\ &= \frac{1}{(2 \pi)^{n/2}} \frac{1}{\sigma^n} \exp\left({-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu)^2}\right) \,, \end{align*}\] and the log-likelihood is \[ \ell(\mu,\sigma \vert \mathbf{x}) = -\frac{n}{2} \log (2 \pi) - n \log \sigma - \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu)^2 \,. \] Because there is more than one parameter, we take the partial derivative of \(\ell\) with respect to \(\mu\): \[\begin{align*} \ell'(\mu,\sigma \vert \mathbf{x}) &= \frac{\partial}{\partial \mu} \left( -\frac{n}{2} \log (2 \pi) - n \log \sigma - \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu)^2 \right) \\ &= -\frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n 2(x_i - \mu)(-1) \\ &= \frac{2}{\sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \mu) \,. \end{align*}\] After setting this quantity to zero and dividing out the term \(2/\sigma^2\), we find that \[ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i = \sum_{i=1}^n \mu ~~\Rightarrow~~ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i = n \mu ~~\Rightarrow~~ \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i = n \mu ~~\Rightarrow~~ \mu = \bar{x} \,, \] and thus \(\hat{\mu}_{MLE} = \bar{X}\). (Recall that as we go from a purely mathematical derivation to a final definition of an estimator, we need to take into account that the estimator is a random variable and thus we need to change from lower-case to upper-case when writing out the variable. Also recall that for this MLE to be valid, the second derivative of the log-likelihood function \(\ell(\theta \vert \mathbf{x})\) at \(x = \bar{x}\) has to be negative. We leave checking this as an exercise to the reader.)

Because the estimator is \(\bar{X}\), we know immediately its expected value and variance given previous results:

- \(E[\hat{\mu}_{MLE}] = E[\bar{X}] = \mu\) (the estimator is unbiased); and

- \(V[\hat{\mu}_{MLE}] = V[\bar{X}] = \sigma^2/n\) (and thus \(MSE[\hat{\mu}_{MLE}] = \sigma^2/n\)).

While \(\hat{\mu}_{MLE}\) is an unbiased estimator, recall that MLEs can be biased…but if they are, they are always asymptotically unbiased, meaning that the bias goes away as \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

Here, we will introduce one more estimator concept, that of consistency: do both the bias and the variance of the estimator go to zero as the sample size \(n\) increases? If so, our estimator is said to be consistent. If an estimator is not consistent, it will never converge to the true value \(\theta\), regardless of sample size. Here, we need not worry about the bias (\(\hat{\mu}_{MLE} = \bar{X}\) in unbiased for all \(n\)), and we note that \[ \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\sigma^2}{n} = 0 \,. \] Thus \(\hat{\mu}_{MLE}\) is a consistent estimator.

The question that we are going to pose now refers to a point made obliquely in the previous chapter: how do we assess \(V[\hat{\mu}_{MLE}]\) in absolute terms? Can we come up with an estimator that is more accurate for any given value of \(n\)?

The answer lies in the Cramer-Rao inequality, which specifies the lower bound on the variance of an estimator (so long as the domain of \(p_X(x \vert \theta)\) or \(f_X(x \vert \theta)\) does not depend on \(\theta\) itself…which is true for the normal). In this work, we focus on determining lower bounds for unbiased estimators, but bounds can be found for biased estimators as well, as shown here.

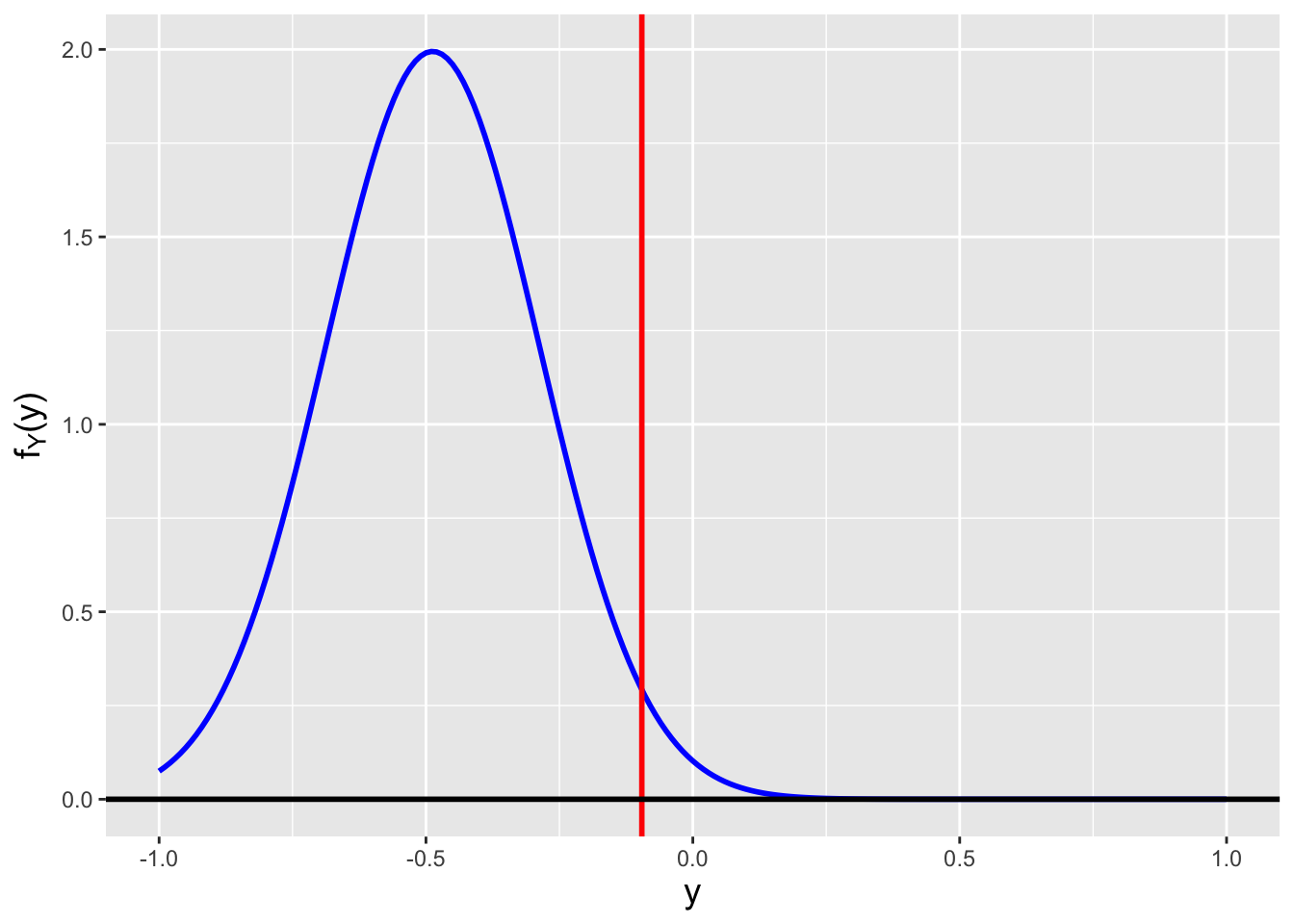

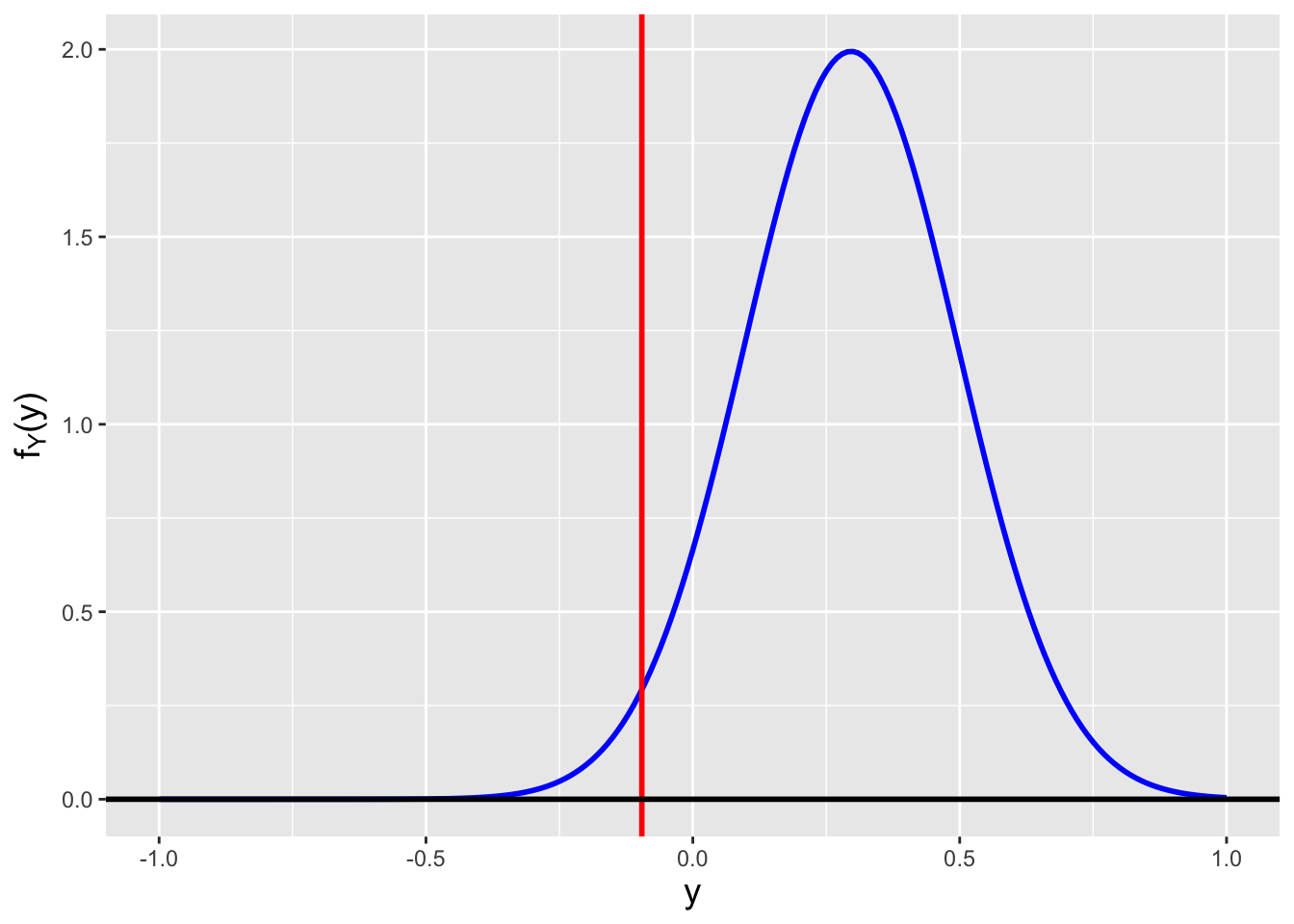

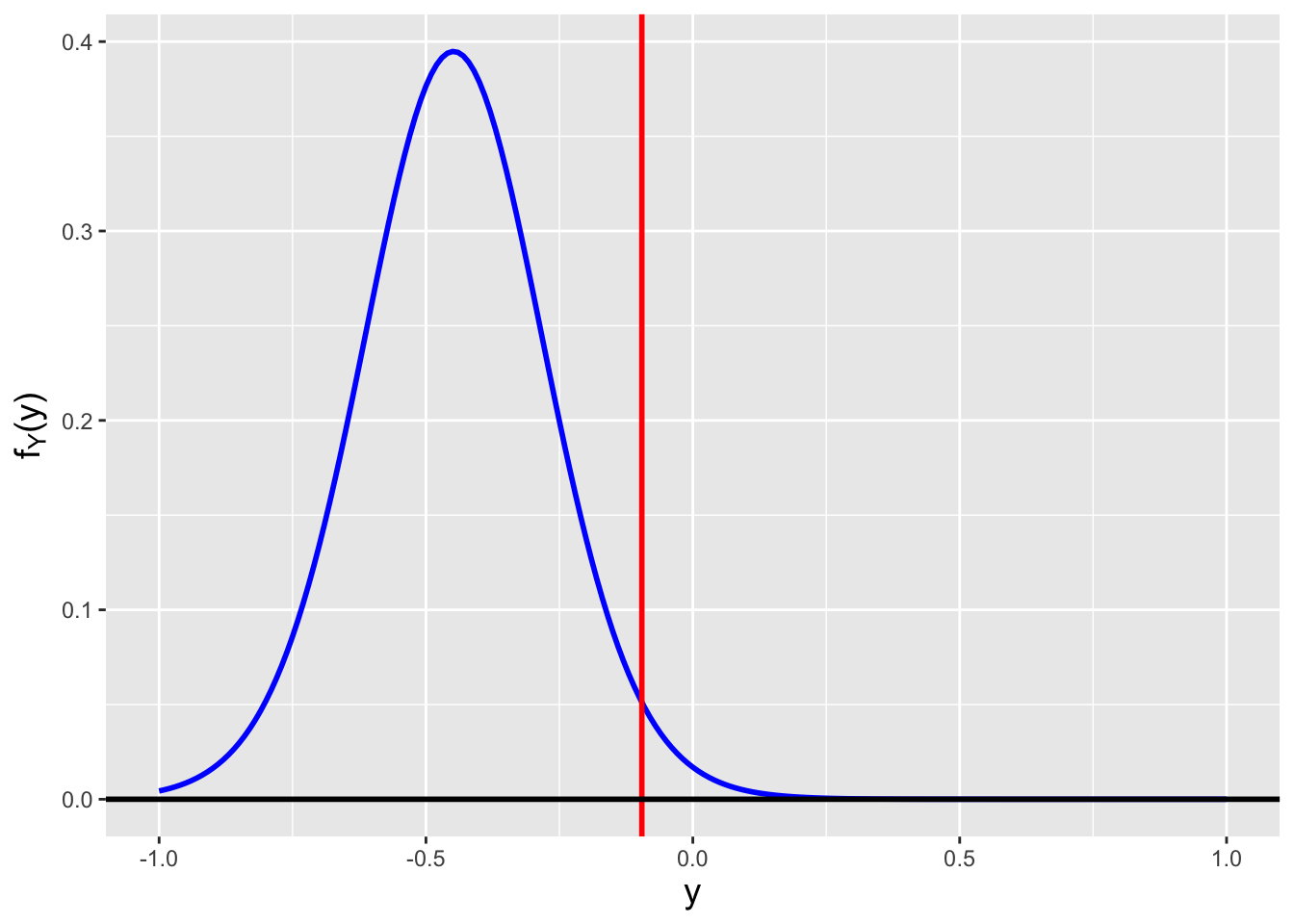

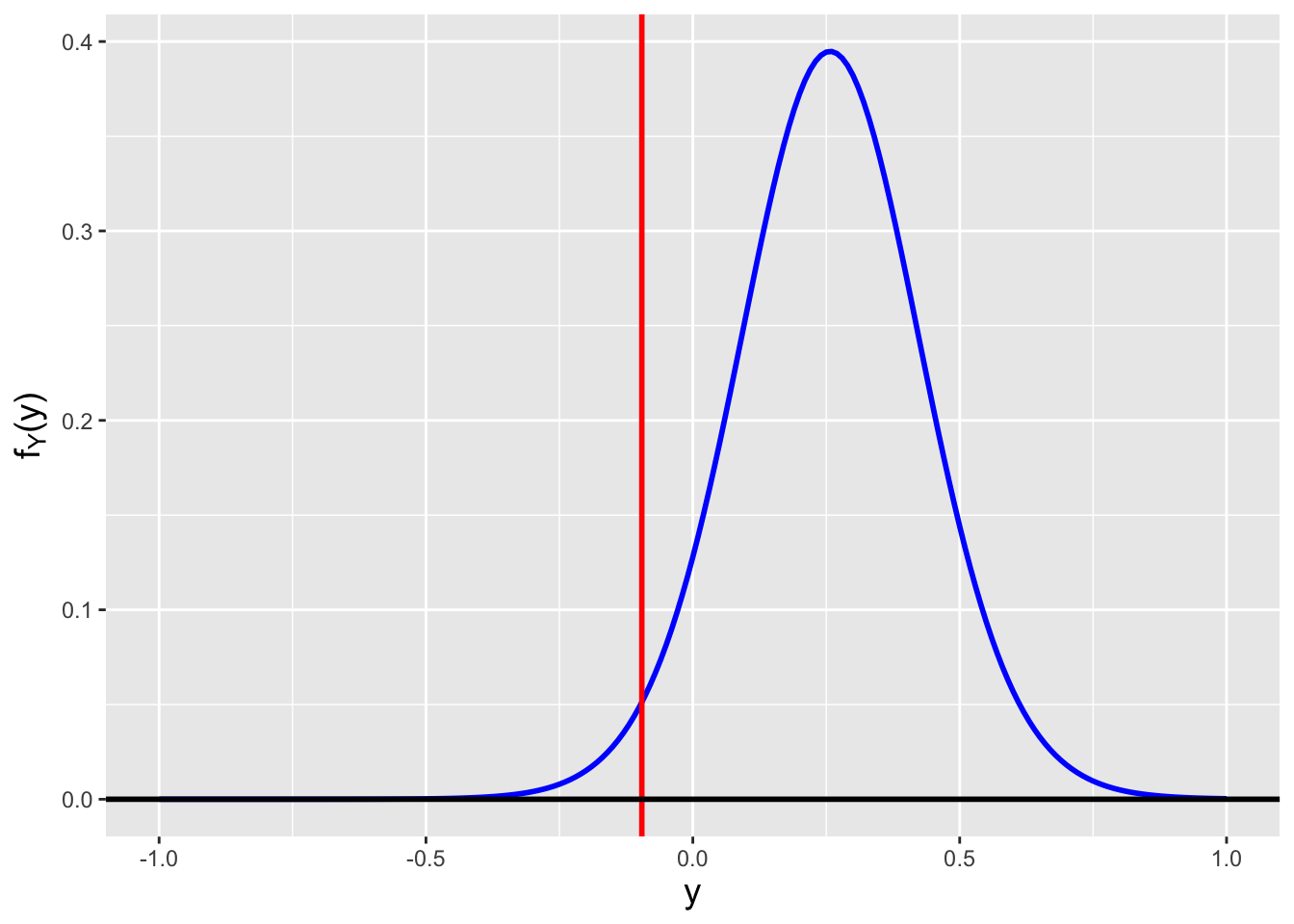

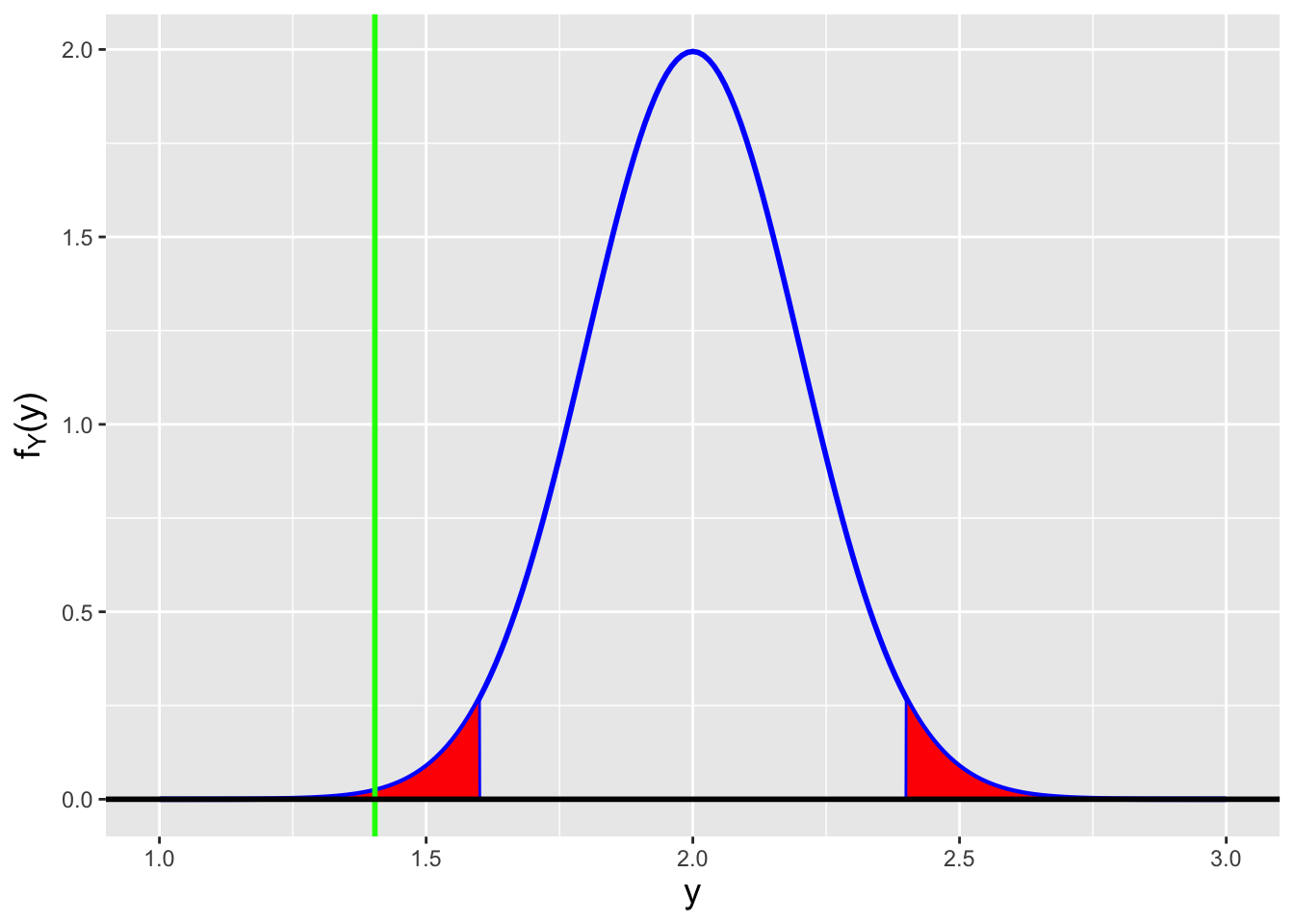

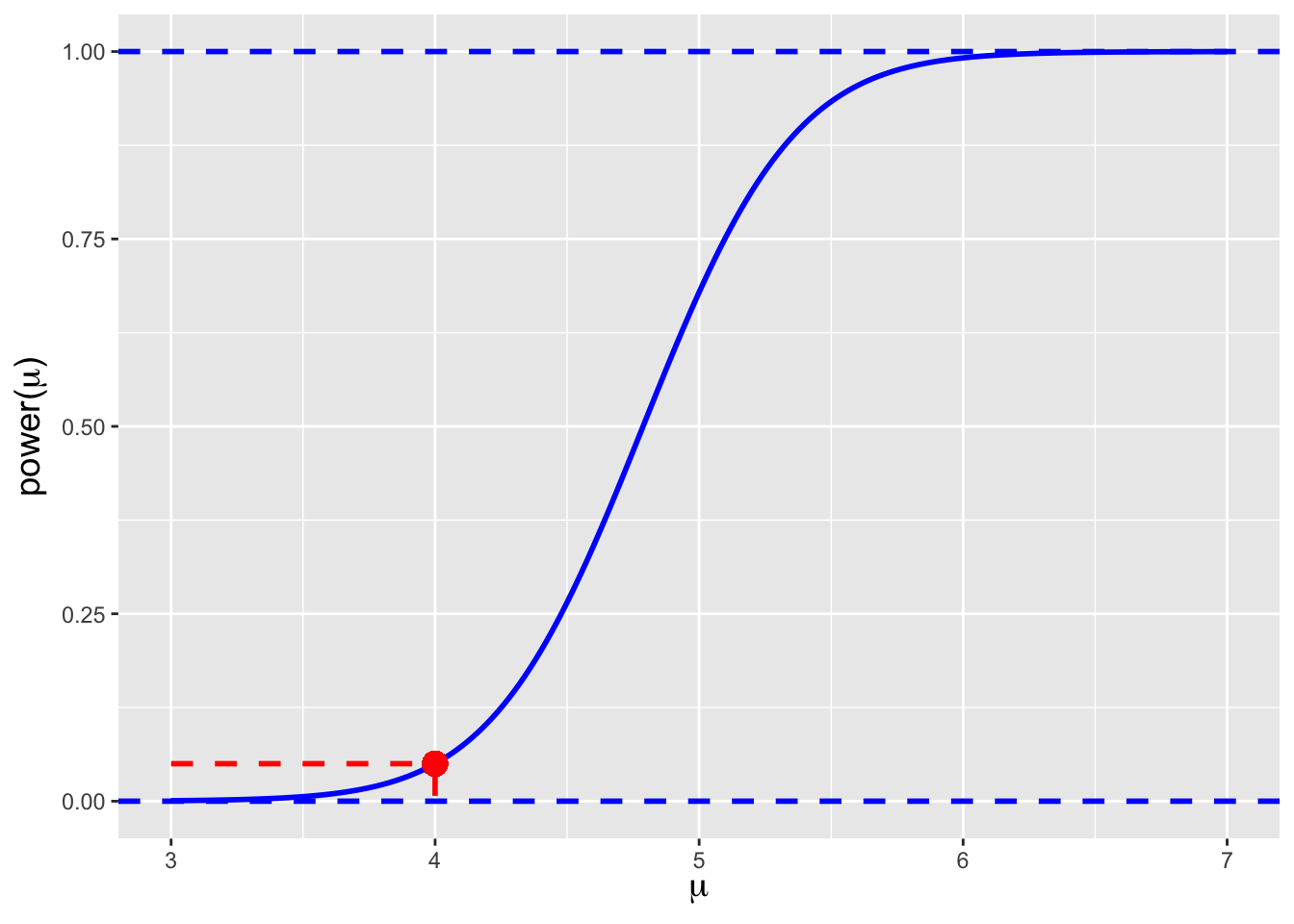

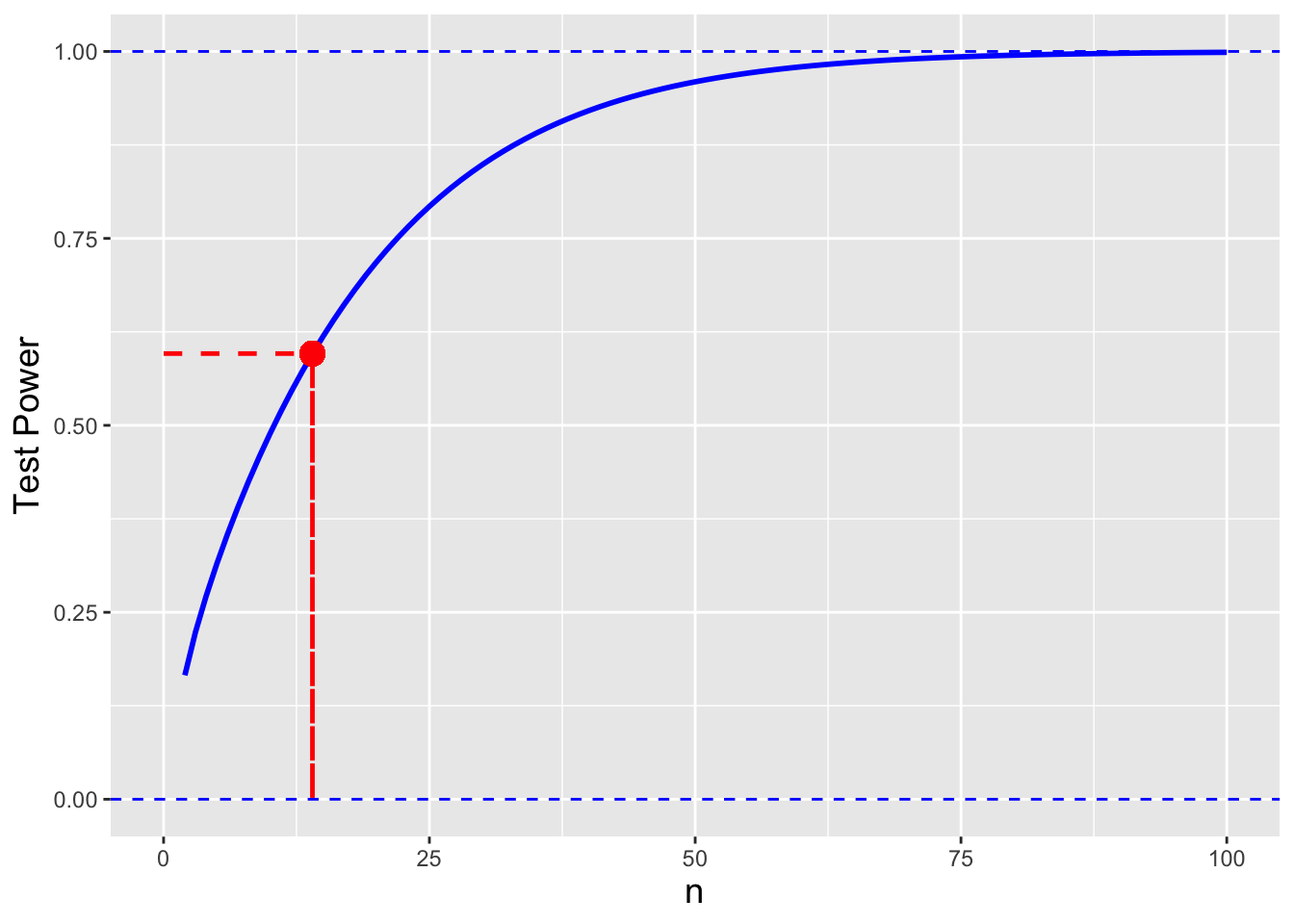

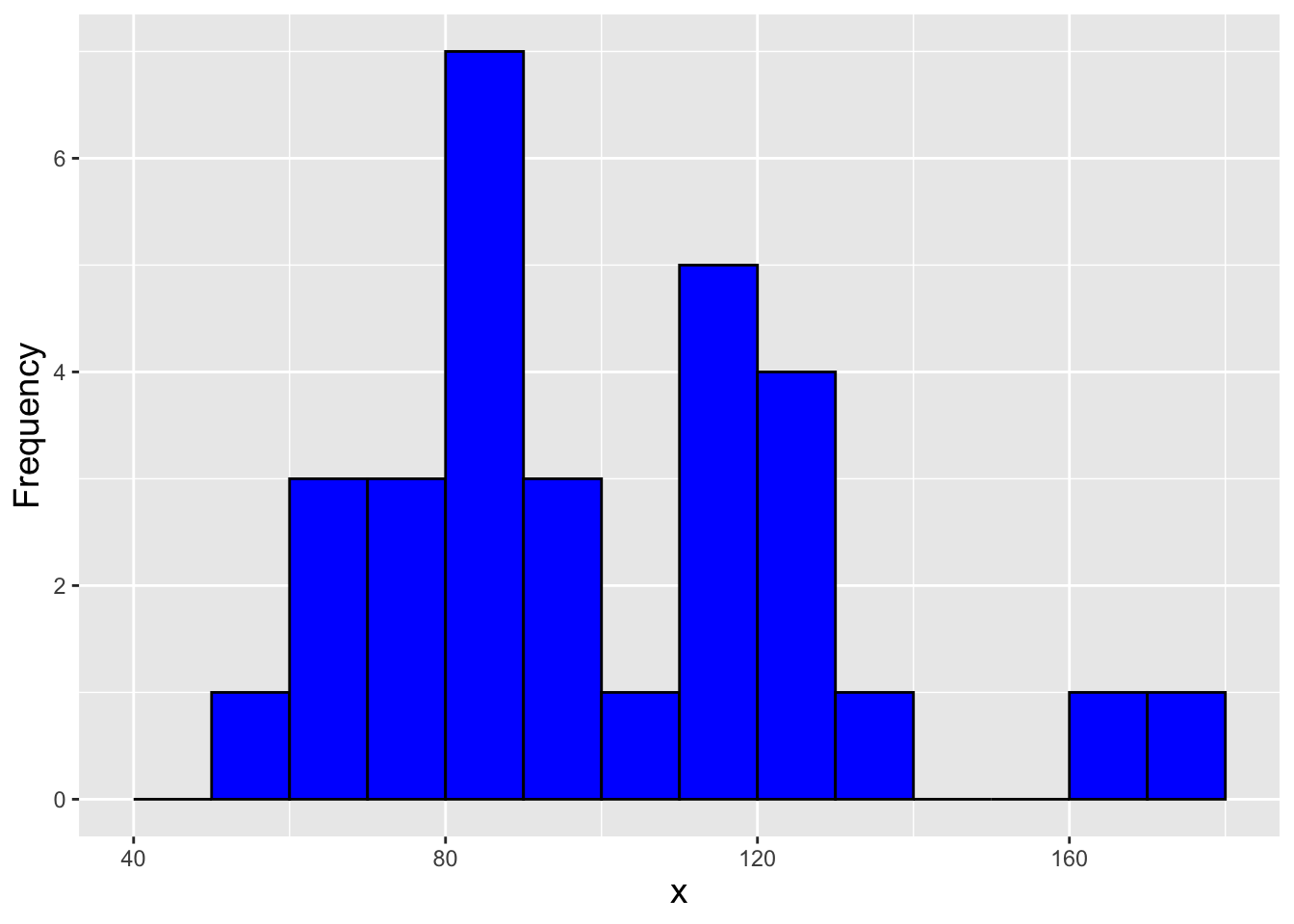

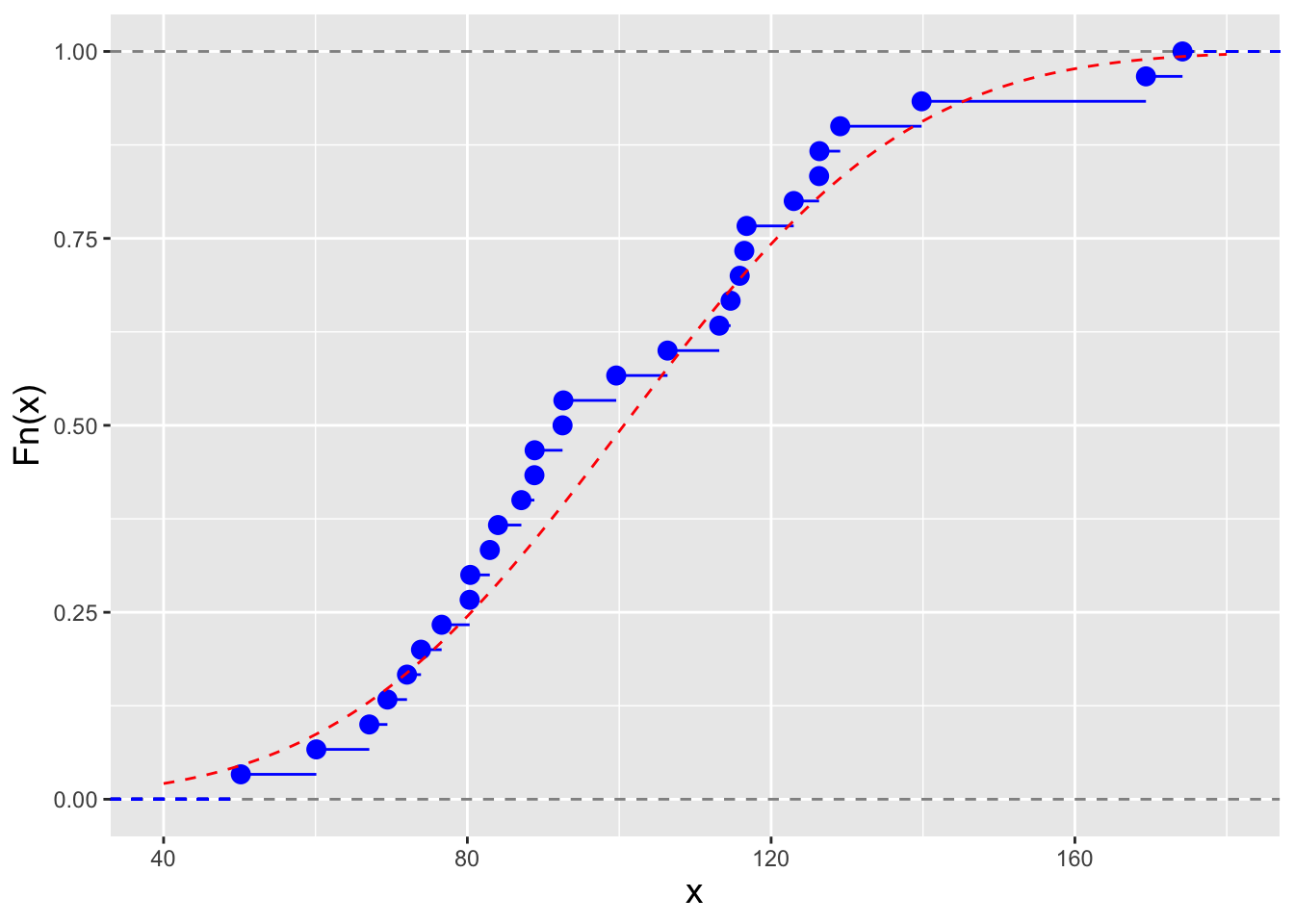

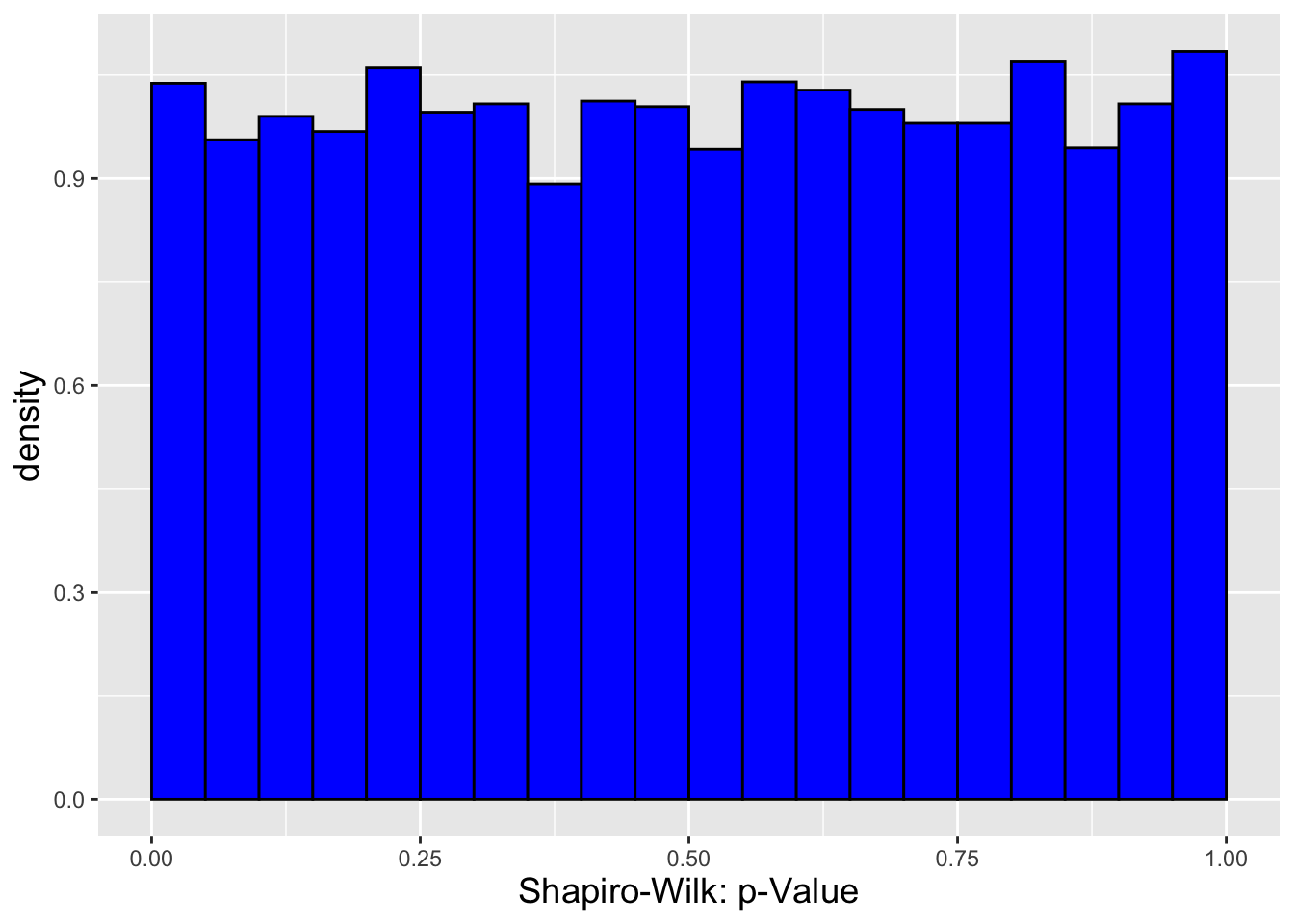

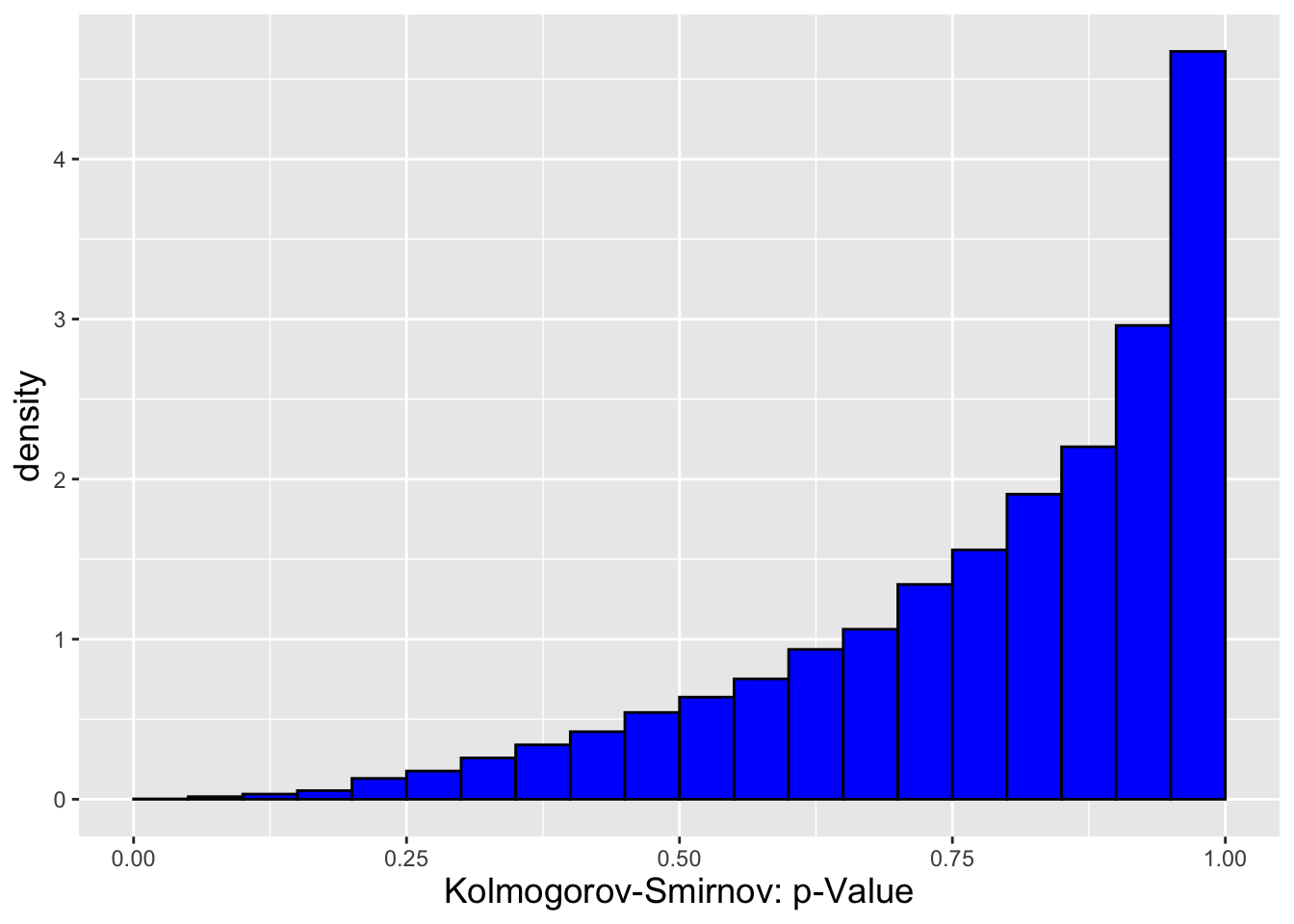

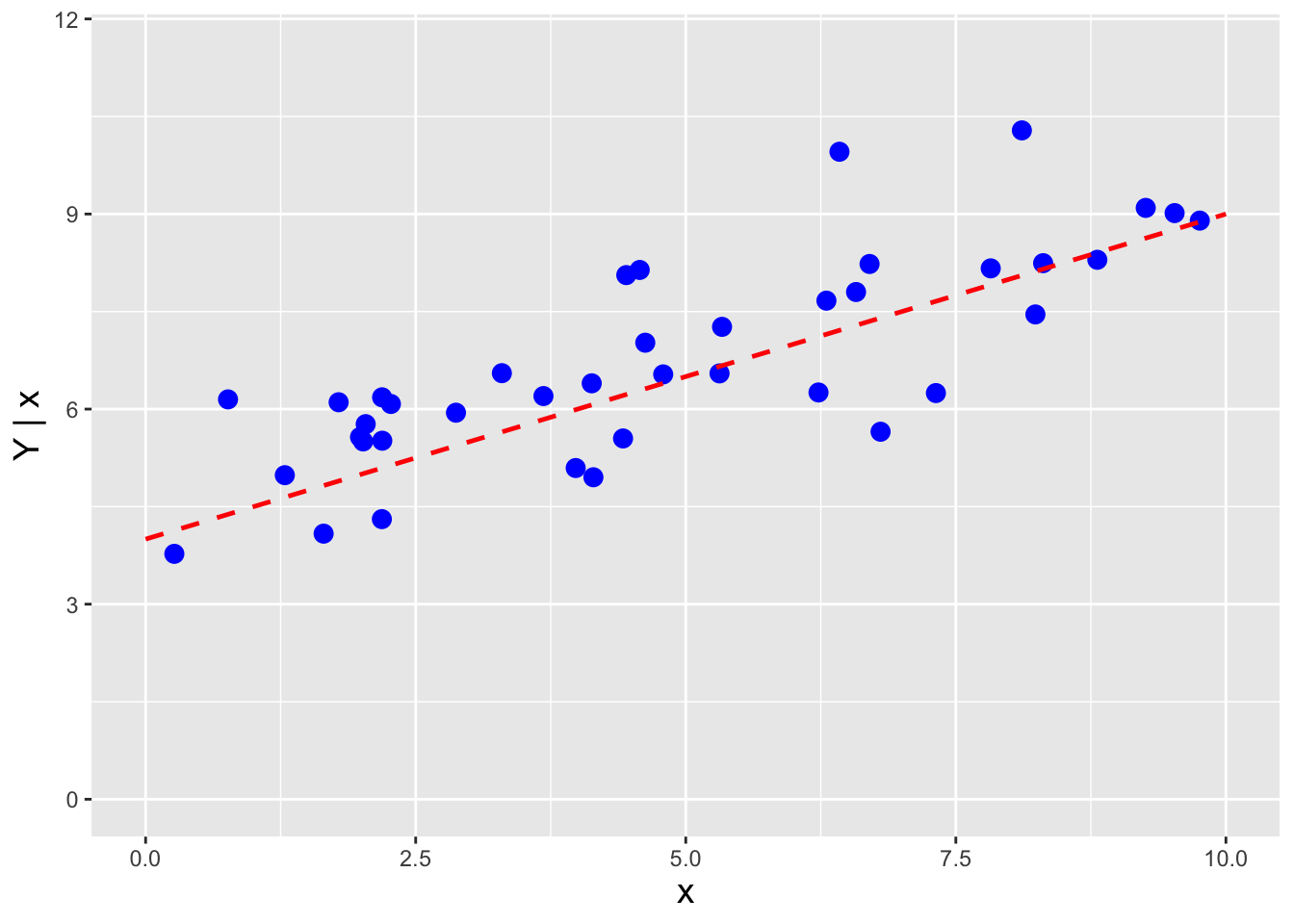

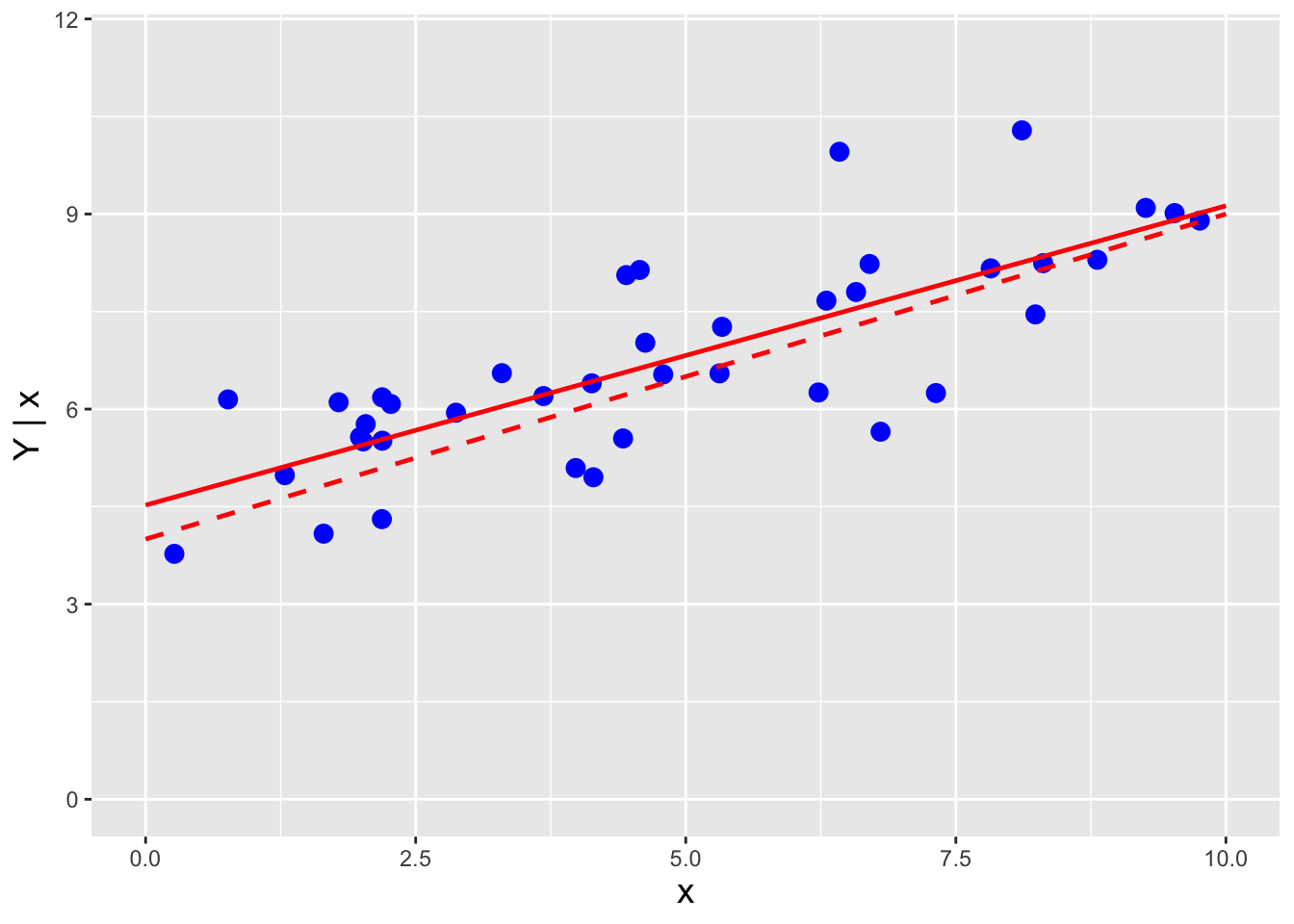

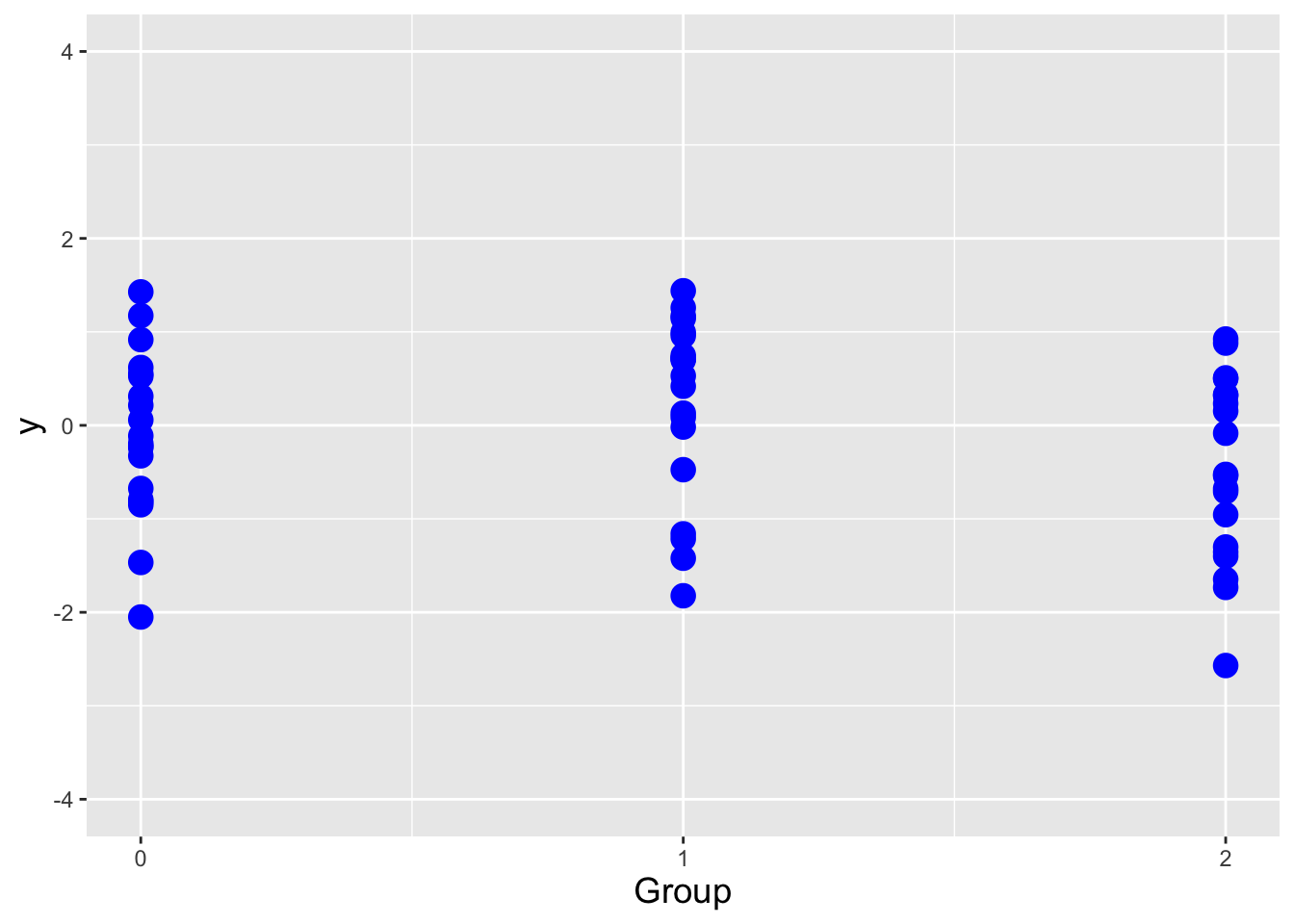

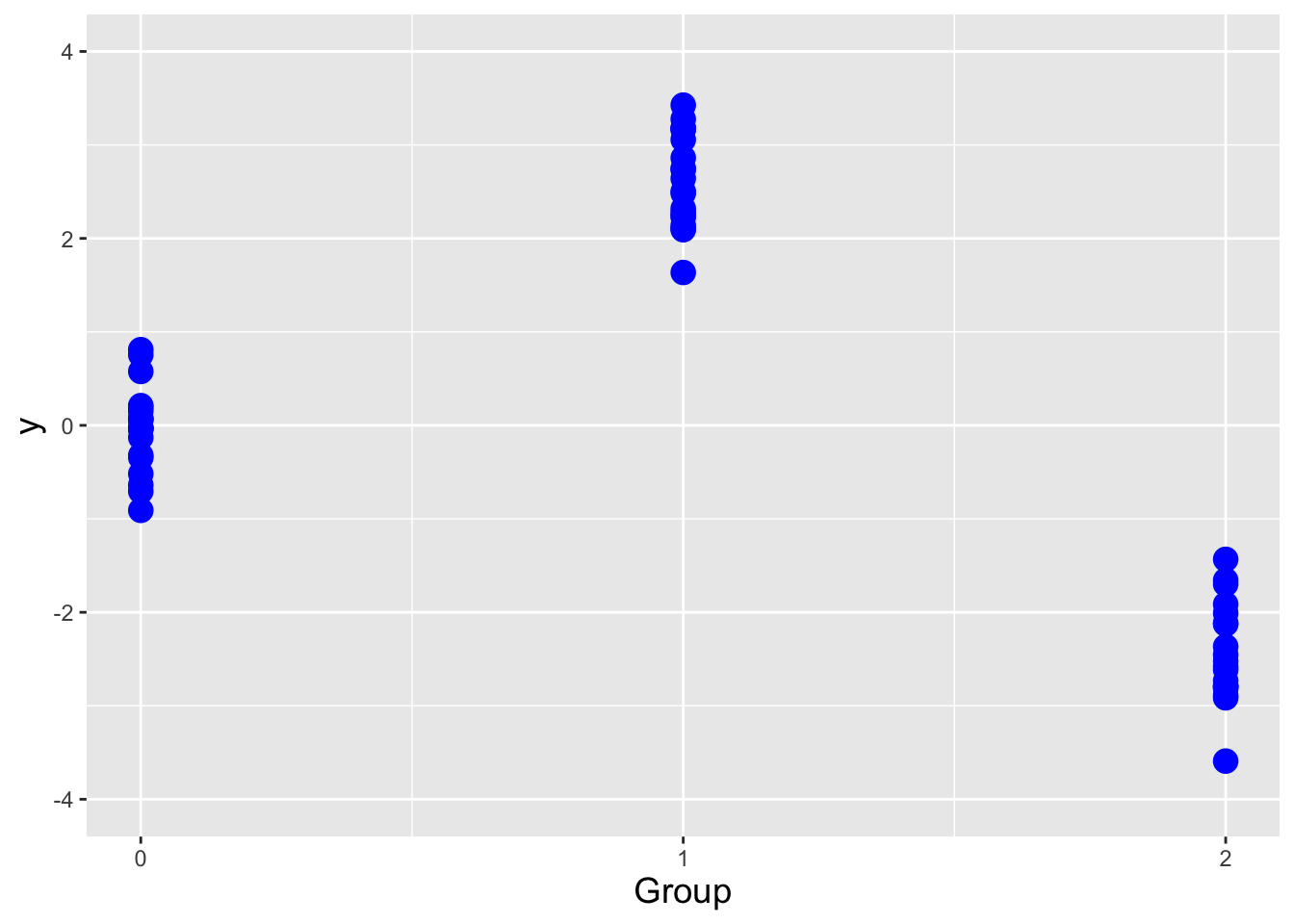

If we sample \(n\) iid data, then the Cramer-Rao lower bound (CRLB) on the variance of an unbiased estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) is \[ V[\hat{\theta}] = \frac{1}{I_n(\theta)} = \frac{1}{nI(\theta)} \,, \] where \(I(\theta)\) represents the Fisher information for \(\theta\) contained in a single random variable \(X\). Assuming we sample our data from a pdf, the Fisher information is \[ I(\theta) = E\left[\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \log f_X(x \vert \theta) \right)^2\right] ~~~\mbox{or}~~~ I(\theta) = -E\left[ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial \theta^2} \log f_X(x \vert \theta) \right] \,. \] (The equation to the right is valid only under certain regularity conditions, but those conditions are usually met in the context of this book and thus this is the equation that we will use in general, as it makes for more straightforward computation.) Let’s step back for a second and think about what the Fisher information represents. It is the average value of the square of the first derivative of a pdf. If a pdf’s slope is relatively small (because the pdf is wide, like a normal with a large \(\sigma\) parameter), then the average value of the slope, squared, is relatively small, i.e., the information that \(X\) provides about \(\mu\) or \(\sigma\) is relatively small. This makes intuitive sense: a wide pdf means that, for instance, when we sample data and try to subsequently estimate \(\theta\), we will be more uncertain about its actual value. On the other hand, if the pdf is highly concentrated, then the average slope of the pdf is larger and…\(I(\theta)\) is relatively large; a sampled datum would contain more information by which to constrain \(\theta\). (See Figure 2.10, in which the pdf to the left has less Fisher information content about \(\mu\) than the pdf to the right.)